Circular economy: From ship to chip, a $500 billion opportunity awaits India – Read the in-depth story on Circular Economy with extensive coverage of Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) and their Partners

Mumbai, 16th December– In yet another significant milestone Circular Apparel Innovation Factory got an extensive coverage on a detailed and in-depth story around Circular Economy and India by ET Prime .

The detailed article quotes Circular Apparel Innovation Factory with insights and perspectives from Venkat Kotamaraju, Director, CAIF and also features their Partners and Collaborators with inputs from Dr. Rachna Arora, Team Leader, GIZ, Marine Litter & EU-REI among other experts and industry leaders.

Synopsis : For a country where reusing and sharing of products isn’t new, India has been unable to streamline or organise the unstructured secondhand market. Such a move will have environmental and economic advantages that can help multiple industries.

In 2007, Rohan Gupta, then a techie with SAP Labs in Bengaluru, decided to upgrade his laptop to one that can keep up with his hectic work requirements. But he didn’t know how to discard the used one in a data-secure and environment-friendly way. So, he called his older brother Nitin, who was doing an MBA from the Stern School of Business in New York, for help.

After some basic research, the brothers were disappointed to find that India had no electronic waste recycler. This led them to set up Attero Recycling in 2008.

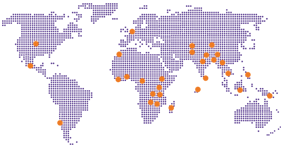

Today, the Noida-based Attero collects and safely disposes of e-waste from over 1,400 cities in India. It has tied up with electronics manufacturers such as Samsung and LG and automobile manufacturers such as Hyundai and Maruti Suzuki to process used devices and parts — either to recycle or dispose of these safely. It wouldn’t be imprudent to call Attero one of the pioneers in formalising the circular economy in India.

Circular economy involves reusing, recycling, repairing, refurbishing and sharing of products. It encourages reusing or recycling a product instead of throwing it away and causing pollution and triggering climate change events. This practice has become a necessity in today’s world. A 2018 FICCI-Accenture report said, “Given the current resource constraints, business-as-usual is not sustainable and there is a need to decouple growth from resource requirements.”

Apart from mitigating environmental problems, the circular economy can also give the country’s economy a boost. The report said that $0.5 trillion ($500 billion) worth of economic value can be unlocked through circular economy business models in India — and $4.5 trillion globally — by 2030. For example, reusing and recycling will help India get access to good-quality raw materials that the domestic industry can use, reducing the dependence on imports.

Potential in Sectors

Giving a glimpse into the potential economic benefits of a circular economy, the study says India can generate $1 billion worth of gold from e-waste. In plastics recycling, it can create 14 lakh jobs and present a $2 billion economic opportunity. Steel recovery from end-of-life vehicles can give 8 million tonnes of steel in 2025, representing a $2.7 billion opportunity.

For Attero Recycling, all this translates to good business potential and also becoming an earth[1]friendly company. The company claims to extract pure gold, silver, copper, iron, aluminium and others, and putting these back into the market for reuse. “More than 90% of the quantity is extracted from Li-ion batteries, and more than 99% from e-waste. Which means that from one gram of gold used in a product, we extract more than 0.99 gm of gold,” Gupta says.

Textiles — a segment where the country is a leading global player — can gain a lot by embracing a circular economy. A research by Water Footprint Network showed it takes 22,500 litres of water to produce 1kg of cotton in India; the global average is 10,000 litres. The fashion industry produces 10% of all humanity’s carbon emissions and is the second-largest consumer of the world’s water supply, according to the World Economic Forum. No one is going to stop buying clothes, and most of the discarded clothes end up in landfills. This makes textiles a prime candidate for a circular economy.

There is increasing awareness and a gradual rise in the interest of apparel waste recycling by fashion and lifestyle brands, experts claim. However, sustainability can be challenging, as the sector has several unstructured and informal players. In India, firms and organisations such as the Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF), Apparel Export Promotion Council and Canvaloop have been working with MSMEs, suppliers, manufacturers and other stakeholders to help them transition towards a circular economy

CAIF — which has tied up with some big apparel players — is focussing on decarbonising the industry and getting to zero-leakage of textiles waste. Venkat Kotamaraju, Director of CAIF, says they are trying to build circular textile waste management models that focus on building skills and capacities among waste collectors. The project is expected to create over 5,000 green jobs, while saving at least 20 million kg of textile waste from ending up in landfills by 2026. While waste collection already happens in textiles, he says they want to create and train a team of informal and underserved waste workers to responsibly collect and segregate waste. The whole aim is to make use of the waste as an input in the upcycling ecosystem.

Surat-based firm Canvaloop is also on a similar mission. It develops fibres by using agro waste and plant materials such as hemp. Canvaloop, founded in 2017 by Shreyas Kokra, claims its fibres require minimal water and have no pesticides or insecticides. It also claims to process around 30 tonnes of agricultural waste every month.

Ship recycling is another segment with immense potential. Maersk, for example, has an initiative in Alang — the world’s biggest ship breaking yard — to collaborate with shipowners and other stakeholders to explore opportunities and incentivise a circular economy. Prashant Widge, Head of Responsible Ship Recycling at Maersk, explains that India has about a third of the global ship recycling market. “About 80% of a ship is steel and 20% is equipment, machinery, the engine, spare parts, etc. A large chunk of the steel is melted and turned into ingots and steel rods, which are then used in domestic construction. This is marine-grade steel. Even after being in the sea for 20 years, it is still strong enough to be reused,” he says. Materials from the rest 20% of the ship are also refurbished and reused. Widge says they use skilled workers to remove hazardous materials and transport these to a downstream waste management facility.

MSME Centric

A circular economy cannot be functional without the participation of India’s 60 million MSMEs and ancillary units. The model is meant for small businesses and MSMEs, claims Manoj Kumar, founder, Social Alpha, an incubator for social entrepreneurs. While large businesses and corporations only drive linear businesses, there are endless opportunities and employment potential among small businesses for circular business.

The challenge is getting them all on a platform to share knowledge and resources. That is what German development agency GIZ is trying to address, in association with the European Union’s Resource Efficiency Initiative (India) EU-REI. Rachana Arora, the leader of the team at GIZ that is involved in the initiative, says, “Small businesses are usually struggling with compliance issues, bureaucracy, etc. But if they actually get a platform where they can actually innovate, create products that are much more efficient, then there is an appetite for this.”

GIZ already works with the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association (ACMA) — which has a lot of SME suppliers in smaller cities — to share the tools for cleaner production practices. A global inclination to reuse and recycle is pushing the auto sector SMEs towards a circular economy. Arora says ACMA came to them and said global auto companies were asking vendors and suppliers about their supply chain and manufacturing practices. “What are the kinds of primary or secondary materials they are consuming? How do they validate their supply chain? There are also questions regarding the greenhouse gases’ mitigation potential. ACMA is working with us on that part, because they would like their SME or suppliers to adopt these practices,” she says.

Even apparel brands, says CAIF Director Kotamaraju, are helping their supply chain partners by giving them access to low-carbon technologies. This way, suppliers avoid the huge cost in acquiring the know-how and there can be a significant reduction in carbon emissions, too. It also makes them a preferred supplier of European brands.

Thriving Informal Market

India has an inherent advantage when it comes to implementing a circular economy. Reusing and sharing of products and a frugal culture are not alien to us. There are several thriving secondhand markets across the country selling reused and refurbished products, from electronics to clothes. Some of these unstructured markets are actually doing very well, says Arora, pointing to Delhi’s Mayapuri as an example. “You can see people coming from across the country to buy a particular part for an old vehicle.”

However, a structured circular economy cannot take root and thrive in the country unless we address some issues. Companies may say they will use a percentage of scrap in production, but that is easier said than done, says Arora. “A lot of industries would like to just go and collect

used materials in the wake of policies like the scrappage policy. But they will require trained manpower to handle those equipments. We need to look at those processes.”

SMEs have to learn to address the occupational health risk before a circular economy can take root. This is because in a passenger vehicle, for example, 75-80% of material can be recovered, but 15-20% of it is toxic that has to be handled in a specialised way.

Attero’s Gupta says the internationally accepted Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) regulation ensures that companies manufacturing and selling products are made responsible for collecting end-of-life waste and making sure it is recycled right. Prior to this and even right now, he claims, a large portion of electronic waste is recycled in the informal sector using hazardous and non-scientific processes. “The average lifespan of people working in the processing of unscientific ways of electronic waste is less than 27 years. Typically, they’re women and children. They’re exposed to cyanide, sulfuric acid fumes, lead fumes…”

But the code has its loopholes. “EPR was passed as a regulation in 2013, but there were no targets fixed. So even if, let’s say, Apple collected one cell phone back, they were compliant. If they collected 100,000 cell phones, they were compliant,” he adds. In India, EPR was made mandatory and targets were rolled out in 2018.

CAIF’s Kotamaraju points out that there is no EPR policy for textiles, though it is the second largest employer and the third most polluting industry in the world. “We need a very considered and well-articulated policy around EPR for textiles.” The lack of policy framing and advocacy is the biggest obstacle in faster adoption of the circular economy, says CAIF’s Kotamaraju.

Kokra says there are infrastructural challenges as well. These can only be solved at an institutional level and not at an individual or a company level. “You cannot go to a farmer and say do like this and give him a contract. You have to be with them.”

People Matters

CAIF is in conversation with industry stakeholders to create visibility on how waste is flowing across the ecosystem. Kotamaraju says it is important to look at how these transitions will affect people.

In Alang, the focus is more on health hazards as ships have a lot of toxic material. Maersk’s Widge explains the company had to take many initiatives including creating a standard framework around ship recycling. While the company has a downstream waste management facility, not all hazardous materials on a ship can be handled at the facility. There are gaps and lapses that need to be fixed. “But having said that, I also know that the Gujarat maritime board and the Indian Red Cross are working on a hospital. I also know that the pollution control board is working on trying to fix these findings. So, there’s work in progress in this regard from the Indian authorities, which is encouraging,” he adds.

Apart from the focus on reuse and recycle, it is time to take the circular economy up by a notch. Developing non-toxic materials such as biodegradable plastic and recyclable textiles has to be a priority.

We don’t live in an idealistic world, so we have to ensure things are balanced well. Fast fashion, for example, is not going to go away, says Canvaloop’s Kokra. “People will always want to buy new things. What we can do is make it more sustainable, more circular. We can sell the same piece of clothing three times by recycling it, by making it biodegradable, by getting into secondhand fashion.”

In short, it is time that all industries become greener if we all want a rosier future.

View full article