A water-starved India by 2050

We are staring at an apocalypse. This can only be averted if efficient practices are integrated into industries and services

The future of water will be a gamble — resting entirely on the way we decide to play the game here on. Either we continue to use water irresponsibly, threatening the very existence of this planet, or we adopt sustainable and smart water management practices to build a water secure future.

Scenario 1: Status quo

By 2050, India’s total water demand will increase 32 per cent from now. Industrial and domestic sectors will account for 85 per cent of the additional demand. Over-exploitation of groundwater, failure to recharge aquifers and reduction in catchment capacities due to uncontrolled urbanisation are all causes for the precarious tilt in the water balance.

If the present rate of groundwater depletion persists, India will only have 22 per cent of the present daily per capita water available in 2050, possibly forcing the country to import its water.

Scenario 2: Smart deviations

Optimists believe that India’s people, some 1.7 billion by 2050 , will have integrated water efficient practices into their daily lives. If the ambitious water sustainability goals set by global industries and governments are testament, we dare say that the world has begun to recognise water as a resource after all.

While beverage giants are focused on returning water to the communities where they manufacture their drinks, food processing players are engaging with farmers and upstream actors to minimise water usage across the supply chain, and textile houses are evangelising the concept of sustainable fashion. Companies have realised the business risks emanating from the possibility of a water-scarce future. This has triggered companies to re-engineer processes, implement water optimising technologies, establish water audit standards, and use a collaborative approach to wade through the water crisis.

There are many examples. Coca Cola and PepsiCo replenish water through community water recharge and conservation projects. SAB Miller helps its partner farmers reduce groundwater use. General Mills is planning to sustainably source 10 priority ingredients by 2020.

By 2015, IKEA achieved its target to use 100 per cent sustainable cotton, grown using less water and chemicals. Levi Strauss has saved over 1 billion litres of water through its patented Water<Less process. Maruti Suzuki’s use of dry wash, and bio degradable chemicals, has enabled a 50-per cent reduction in water used for car washes.

Water-efficient technologies will continue to be developed like they already are today, but more importantly, it is the renewed understanding of water as a shared commodity that will help these technologies find acceptance with industries, agriculture, and individuals alike.

New habits will be created over the coming decades and efficient water usage will be synonymous with all users. To help visualise this future, we have drawn out interventions that will have become second nature to the country’s populace and found large scale use in India by 2050.

Efficient water use

Agriculture will continue to be the mainstay of India in 2050. However, what is going to markedly change is the utilisation of water by the sector — efforts of which have already begun to take shape, reflected in the country’s ‘per drop-more crop’ mantra. Currently, the world’s leading virtual exporter of water, India will have integrated water efficient practices into the way it farms. Produce yields will not take a beating, instead, data-driven farming will enable efficient water utilisation.

A number of these technologies are already in play: soil sensors that analyse moisture content of soil and relay the information to a cloud based platform, which in turn controls the amount of water released to crops; drone enabled thermal imaging of farms that help in predicting the temperature and water requirement of crops; and IoT sensors that detect leakages in irrigation pumps and pipes and automatically plug the leaks.

Industries will be judged by their shareholders and customers on environmental sustainability practices integrated into core business operations. As a result, industries will reduce their dependency on freshwater altogether. Treatment of waste water and the use of recycled water in manufacturing products will be prevalent across industries.

Innovative technologies that reduce water will be used in operations — for instance, Nike and IKEA backed DyeCoo Textile Systems swaps water intensive dyeing processes with a carbon based process, where carbon dioxide is transformed into liquid at high pressure and heat and this liquid is used for dyeing fabric.

As an unexpected by-product of hydraulic fracturing industry, there has been a high demand for highly mobile waste water treatment facilities. Investments are being channelled into facilities which can treat waste water. With higher volumes of water and technology improvements, the prices can be kept at optimal levels.

Shared goals

Technology will have incredible impact on domestic water consumption. Leaky taps will no longer be a problem with users being able to remotely shut off valves using ‘smart meters’. Behaviour change in water utilisation will be driven through gamification models that will score households in comparison to their neighbours; smart meters linked with mobile apps will rank users on their water usage patterns.

Flush-less urinals, solar-powered flushing systems, dirt-sensor taps, and self-cleaning surfaces will be standard fixtures in homes, offices, and public institutions. Off-grid atmospheric water generators, like that being prototyped by Uravu Labs, and ‘self-filling’ biking bottles that produce water as you pedal, will create water from thin air.

While countries such as Australia have made water a tradable commodity, it could become a norm in most countries by 2050. Strategies, forms, pricing may differ across countries, however, water trading through financial instruments could be a common thread, primarily because of its inter-linkages with agriculture and energy.

Water availability will be treated as a national security issue, like in the case of Israel, thus providing the impetus to make it a priority. Coastal regions will be more dependent on sea water by using desalination technologies. Simpler and cheaper solutions like rain water harvesting mechanisms, which have been in existence since A.D. 550 would be routine forms of accessing water.

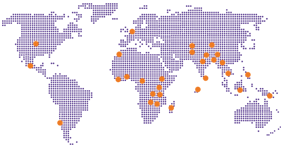

As of now, the narrative suggests a bleak water future and that by 2050 almost 50 per cent of the world’s population will be living under extreme water stress. While this may be true if the current usage (read ‘exploitation’) continues, people armed with technologies and an appreciation of shared risks of water will ensure that stress levels are minimised. Engineered solutions may be the answer to our water woes. However, the success in securing a water safe future will always be tied to the ability to use water a shared resource.

Menon is an associate vice-president and Poti is a manager with Intellecap Advisory Services