-

Times of India

| May, 08, 2023The significance of the UN Sustainable Development Goals for sustainable investing – Shruti Deora, Partner, Intellecap featured in Times of India

Read More -

Impact Entrepreneur

| April, 26, 2023Intellecap & IDH Blog | Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems

Read More -

Times of India

| April, 24, 2023The Role Of Sustainable Investing In Contributing Towards A Greener Future

Read More -

Impact Entrepreneur

| April, 24, 2023Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems

Read More -

The Hindu Business Line

| April, 18, 2023India seeks global alignment around innovative SDG startups: Listen to Vineet Rai, Founder, Aavishkaar Group, and member of the ‘G20 Start Up 20 Engagement Group’ on the HBL Podcast.

Read More -

Sankalp Dhaka Summit

| March, 29, 20231st Edition of the Sankalp Dhaka Summit 2023: Award Winners, Media Coverage & Updates

Read More -

Times of India

| February, 12, 2023Building the supply chain infrastructure for a Circular Apparel industry

Read More -

Livemint

| January, 24, 2023Voluntary carbon trades to start in 2023 -Intellecap report featured in Mint

Read More -

startup20india

| January, 23, 2023Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group joins the Sustainability Task Force as part of G20 India Presidency

Read More - Lack of the implementation of a cohesive milestone-based strategy to decarbonize the supply chain, as well as operations.

- Poor availability of commercially scalable circular, low-carbon technologies that are in sync with the decarbonization needs of the T&A industry.

- Limited awareness and technical capability to measure, report, and set decarbonization goals as per the Science Based Targets

- Emission Mapping & Profiling: Understanding and quantifying carbon emissions across the supply chain, product impact & climate change risks and developing BAU projections.

- Set Roadmap and Create Targets: Developing sustainability strategies, targets and roadmaps at process and organization level, aligned with science and business requirements.

- Reduce Footprint: Identifying & deploying best available technology solutions (input materials, energy efficiency, water mgmt. waste to value, etc) that perform better than the benchmarks; adopting global best practices.

- Adopt offset mechanisms: Address hard-to-abate emissions through off-setting projects such as investing in impact funds, identifying climate finance solutions, etc

- Improvement in energy efficiency: 15 to 20%

- Reduction in process heat: 25%

- Water Recovery: Up to 95%

- Reduction in chemical & biological effluents: 50 to 75%

- Provided end-to-end traceability for ~850 Tons of Textiles waste (2x manufacturers; 4 months)

- Solutions indicated a payback period of 2 to 3 years

(work to measure the impact on carbon footprint is currently in process) - The ability of CAIF to source and evaluate high-potential innovative solutions

- Technical assistance provided by CAIF to innovators (from problem-solution through product-market fit) and the capacity building support provided to manufacturers and supply chain partners

- Provision for a pool of capital available for both innovators and brands /manufacturers to cover the cost of demonstration pilots that expedited approvals & enabled collaborations

The significance of the UN Sustainable Development Goals for sustainable investing – Shruti Deora, Partner, Intellecap featured in Times of India

Shruti Deora, Partner, Intellecap’s article, was featured by Voices, the Times of India blogs. The article highlights how the SDGs provide a powerful framework to create long-term value and how as we move towards 2030, it is essential that we all play a leadership role in achieving them to create a more sustainable and equitable world.

Intellecap & IDH Blog | Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems

As climate change accelerates, transforming agriculture and food systems to reduce emissions has become a global imperative. Technologies for a net-zero transition in agriculture and food systems are playing a critical role in complementing existing climate action initiatives.

Intellecap & IDH are jointly studying these technologies to better understand their potential use-cases in mitigating emissions and how they can be integrated into businesses, governments, and developmental agencies’ strategies.

This article provides an overview of the ongoing study and highlights some early findings related to emission hotspots, technology use-cases, benefits, and principles related to adoption in the smallholder context.

A Farmer’s Struggle: The Impact of Climate Change on Smallholder Agriculture

Imagine a smallholder farmer in a low-income country, let’s call him Rajiv, who has been cultivating maize for generations on his family’s land. Over the years, he has witnessed the effects of climate change firsthand. Erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and the increasing prevalence of pests and diseases have made it more challenging for him to maintain a stable crop yield. The rising cost of fertilizers and other farm inputs has only added to his financial burden. Rajiv is aware that his agricultural practices contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, but he feels powerless to change the situation.

Rajiv’s story illustrates the challenges faced by smallholder farmers worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These farmers are not only struggling to adapt to the changing climate but also grappling with their role in the global emissions problem. The urgent need for net-zero transitions in agriculture and food systems calls for innovative solutions that address the unique challenges faced by farmers like Rajiv……

The Role Of Sustainable Investing In Contributing Towards A Greener Future

Mumbai, 24th April– Shruti Deora, Partner, Intellecap’s article on ‘The Role Of Sustainable Investing In Contributing Towards A Greener Future’ was featured by Entrepreneur India.

On the occasion of Earth Day, Entrepreneur India examined how incorporating gender lens investing and climate finance into sustainable investing practices can boost growth, profitability, and foster a greener, more gender-inclusive, and climate-resilient future.

Sustainable investing is gaining momentum as investors recognize its potential for financial returns and positive social and environmental impacts. This Earth Day, we’ll examine how incorporating gender lens investing and climate finance into sustainable investing practices can boost growth, profitability, and foster a greener, more gender-inclusive, and climate-resilient future.

Sustainable investing, also known as responsible or values-based investing, involves considering environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors in investment decisions rather than relying purely on financial considerations. The business case for sustainable investing is well established. Recent research from Bain & Company and Eco Vadis also shows that sustainability initiatives correlate with financial performance, sustainable supply chains, renewable energy usage, employee satisfaction, and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI).

Despite challenging market conditions in 2022, sustainable investment funds experienced net positive fund flows of $115 billion, according to the Morgan Stanley Institute for Investing’s Sustainable Reality report. CareEdge Research shows that ESG reporting by Indian corporates has jumped by 160% basis reports from top 1,000 listed entities over the past three fiscal years with 18% companies voluntarily disclosed the BRSR data in FY22.

Gender lens investing is an important subset of sustainable investing that promotes gender equity and inclusion. Studies indicate that empowering women could significantly lower global carbon dioxide emissions by 2050. Companies with over 30% female board representation have reported lower carbon emission growth rates, reduced energy consumption intensity, decreased greenhouse gas emissions, and less water usage.

Climate finance plays a crucial role in promoting a greener and more climate-resilient future. The International Energy Agency asserts that annual clean energy investments must increase from $1.3 trillion in 2021 to above $4 trillion by 2030 to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Climate finance can help mobilize the capital needed to support the transition to a low-carbon economy and enhance climate resilience. Climate Investment Funds have raised over $11.1 billion in climate finance and supported more than 390 projects in developing countries. Companies like Tesla and Beyond Meat have seen significant growth and profitability by prioritizing sustainability and ESG factors. Climate finance in India totalled a whopping ~USD 44 billion per annum for 2020, but reports estimate that for India to achieve its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, we require USD 2.5 trillion per year up to 2030.

Agence Française de Développement (AFD), the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI), and the Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation have recently launched GroW – Greening of Finance by Women as part of the Green Indian Financial System (GIFS) Initiative, aimed at advancing and leveraging women’s participation, leadership, and knowledge in green and climate finance, with the vision to create a gender-equitable green and climate finance sector and address these gaps.

Sustainable investing presents multiple new opportunities for entrepreneurs to contribute to a greener future. By prioritizing sustainability and ESG factors in their business practices, entrepreneurs can reduce their environmental impact and drive positive social and environmental outcomes. For instance, entrepreneurs can adopt renewable energy sources, minimize waste generation, and focus on sustainability in their supply chain by selecting environmentally friendly materials and reducing carbon emissions. These practices can improve overall sustainability performance, reduce reputational risks, and attract sustainable-minded customers and investors.

The increasing demand for sustainable products and services offers new business opportunities for entrepreneurs. By creating innovative solutions that address social and environmental challenges, entrepreneurs can tap into new markets and drive innovation. Examples include developing energy-efficient technologies, sustainable agriculture practices, clean transportation, sustainable fashion and beauty products, sustainable food products, and eco-friendly building materials. These innovations can cater to the growing demand for sustainable consumer goods and contribute to a greener future.

While there are concerns about “green-washing”, regulatory standards are being established globally to address and streamline the measurement and reporting aspects of sustainability initiatives. Sustainable investing is growing exponentially and is expected to become the new normal within a decade. By integrating gender lens investing and climate finance into sustainable investing practices, investors and entrepreneurs can drive positive change while generating financial returns. Millennials are more conscious of the environmental and social impact of their investments and purchasing decisions. This awareness has led to a growing preference for companies that prioritize sustainability and ESG factors. The quote from Sir Christopher Hohn, founder of TCI Fund Management, captures this sentiment: “Investing in a company that doesn’t disclose its pollution is like investing in a company that doesn’t disclose its balance sheet.” As more investors and consumers demand transparency and accountability, companies that embrace sustainable practices are better positioned to attract capital, talent, and customers. This shift in consumer behaviour will drive businesses to adopt sustainable practices, resulting in a greener, more gender-inclusive and climate-resilient future.

Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems

Tune in Now –http://ow.ly/NgOE50NHUMq

India seeks global alignment around innovative SDG startups: Listen to Vineet Rai, Founder, Aavishkaar Group, and member of the ‘G20 Start Up 20 Engagement Group’ on the HBL Podcast.

Tune in Now –http://ow.ly/NgOE50NHUMq

1st Edition of the Sankalp Dhaka Summit 2023: Award Winners, Media Coverage & Updates

Dhaka, March 22nd, 2023: In a significant milestone, Sankalp Forum, an initiative of Intellecap, and one of the Global South’s largest convening on impact entrepreneurship and sustainable development, hosted its 1st Edition of the Sankalp Dhaka Summit, at the Sheraton Dhaka on the 19th March 2023.

Presented by Aavishkaar Group and Intellecap, the Dhaka Summit positively engaged 50+ Global & Regional Speakers and over 180 pioneering change-makers from the development ecosystem and impact community, to discuss, define, and drive forward the critical levers of entrepreneurial success, across 12+ interactive sessions.

This year’s summit, was themed around ‘Catalysing Bangladesh’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem” and the Keynote Speaker Zunaid Ahmed Palak, State Minister, ICT Division, Govt of Bangladesh highlighted the govt’s commitment to supporting startups and shared his enthusiasm for collaborating further the Aavishkaar Group.

The Opening Plenary with Jayesh Bhatia, MD, Intellecap, Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group, Dr. Naresh Tyagi, Chief Sustainability Officer, Aditya Birla Fashion & Retail Ltd., Sami Ahmed, MD, Startup Bangladesh, ATM Tahmiduzzaman, United Commercial Bank PLC. and Ms. Sonia Bashir Kabir, Founder & MD, SBK Tech Ventures, further emphasized about building the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

At the exclusive press meet during the Summit, Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group spoke about the limitless opportunity that startups and enterprises in the region can uncover. Sami Ahmed, MD, Startup Bangladesh shared his vision as well.

Jayesh Bhatia, Managing Director, Intellecap announced the Bangladesh Green Enterprises Ecosystem Initiative which will raise USD 250 million dollars for 1000 Impact Enterprises by 2030, and will help create 10000 jobs in the country. He also emphasized Intellicap’s engagement with the Government initiatives, and offered to bring in experiences from India to bear on the Bangladesh well-articulated Smart Vision 2041 championed by the Honourable Prime Minister.

Jayesh also referred to the work being done by Intellecap on the Renewable Energy (RE). Solar energy presents huge impact and investment potential with solar power potential making up 50% of the RE target for 2041.

Venkat Kotamaraju, Director, Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) spoke about the significant work CAIF is doing in the RMG space and about the 4th CAIF Conclave, where CAIF through its session, featured some of the top names in the sector, highlighted ideas that can help accelerate the green transition of MSMEs in the RMG Sector and deliberated around the imperative need for skilling for a green and circular transition and shared ideas on how to mobilize and build this ecosystem, all with a view to elevate Bangladesh’s position in the global value chain.

The summit’s key partners were United Commercial Bank PLC (Bangladesh), UCB Investments Ltd. (UCBIL), Startup Bangladesh Ltd., Bangladesh Angels Network, International Finance Corporation (IFC), Doen Foundation, UNDP, UNICEF, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Ltd. (ABFRL) and Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN) , to name a few. The Business Standard was the exclusive media partner to the Summit.

The Summit also witnessed a fireside chat with Vineet and Arif Khan, Vice Chairman, Shanta Bank Asset Mgmt, and compelling sessions on topics such as Promoting Climate Smart and Sustainable Agriculture in Bangladesh, led by International Finance Corporation (IFC), Promoting responsible business approaches for achieving health outcomes by UNICEF, Role of SMEs in Sustainable WASH outcomes by Water.org, Future of Health Care Models by Better Stories and Business Innovations to transform food systems in Bangladesh by Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). In addition, there were learning sessions by way of Master classes and a LIVE deal room where regional and global investors connected with private sector enterprises to facilitate growth capital.

This year the winners of the 1st Sankalp Dhaka Awards 2023 were Wander Woman (2nd Runner-up) PriyoShop (1st Runner-up) and iFarmer (Winner).The other finalists were MommyKidz, Bhumijo, Garbageman and Vertical Innovations.

10th Sankalp Africa Awards Winner 2023

Nairobi, March13th, 2023: Sankalp Forum, an initiative of Intellecap, one of Africa’s largest convening on impact entrepreneurship and sustainable development, hosted its 10th Edition of the Sankalp Africa Summit, at the Kenya School of Monetary Studies, from the 1st and 2nd of March 2023.

Every year, the Summit recognizes and rewards high impact enterprises from a pool of promising finalists, in the Africa region which are tackling key development challenges. The finalists also get the opportunity to pitch their enterprises to a jury panel comprising of eminent business leaders and investors.

This year the winners of the 10th Sankalp Africa Awards 2023 were four most innovative young entrepreneurs in Africa, whose ideas are well poised to deliver significant impact outcomes, whilst solving some of the most complex social challenges. The 10 outstanding finalist impact enterprises representing the region were– Vetsark, an agri startup, Zivanae Afya Bora, a healthcare startup and ThinkBikes, a Circular Economies startup, all from Nigeria, Omajalands, an agri startup from Zimbabwe, Hearty Engineering, an agri startup from Ethiopia, Kwikbasket and Afriagrimark, both agri startups from Kenya, Agki Medical Laboratory, a healthcare startup from Tanzania and Legendary Foods, an agri startup from Ghana.

The Sankalp Africa Awards 2023 Winner was Legendary Foods from Ghana. A food tech startup, Legendary Foods (LF) is on a mission to produce West & Central Africa’s most cost-effective, nutritious, resource-efficient and accessible form of protein, palm larvae, with technology and farming systems proudly built in Ghana.

The First Runner Up was Vetsark Limited from Nigeria. An agri financing startup, Vetsark helps farmers and agribusinesses in Africa access finance, increase productivity, and improve their profitability. They bridge the gap between farmers and financial institutions and is helping unlock the potential of African agriculture by providing farmers with the financing and support they need to grow their businesses.

The Second Runner Up was Agki Medical Laboratory from Tanzania. A healthcare startup, Agki Medical is working to solve the problem of Anemia in pregnant women and children under the age of five living in rural communities. It uses an Electric car to offer a digital mobile dispensary for rural patients by providing affordable laboratory tests for diagnosis, clinics, medications for treatments and Free Health education.

In a unique format the Fourth Winner, called as the ‘Sankalp Ecosystem Award’ is given through a voting process from practitioners from the developmental ecosystem. This year the winner was Hearty Engineering from Ethiopia, an agri tech startup that provides an Intelligent and IoT supported technology device that helps monitor and treat Livestock’s health thereby showing how innovation can make significant impact when wrapped in technology.

“Sankalp today, in its 10th year in Africa, celebrates a decade of impact and the Sankalp Africa Awards has truly been a regional trailblazer when it comes to identifying and supporting hundreds of impact enterprises whose business promise and potential is a crucial to solving economic and development challenges. This year we were once again inspired by the ideas and the cutting edge innovation of our winners, each of whom demonstrate the ability to drive action and influence positive outcomes,” said Arielle Molino, Sankalp Lead and AVP Intellecap Africa

The Summit, supported by Visa Foundation, GIZ, Villgro Africa, FSD Uganda, US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and Energy Catalyst, engaged over 1,400 stakeholders, from 70+ countries around the World, including participants from 40+ African countries.

Building the supply chain infrastructure for a Circular Apparel industry

Mumbai, 13th February –Siddharth Lulla, Principal, Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF), Intellecap was recently featured on the Times of India blogs through his article, “Building the supply chain infrastructure for a Circular Apparel industry” which highlights how CAIF is working with upstream supply chain partners primarily SMEs to reduce carbon emissions,

Under the aegis of UN Climate Change, brands and retailers worked during 2018 to identify ways in which the broader textile, clothing and fashion industry can move towards a holistic commitment to climate action. As a result, industry players made bold commitments to enable circularity, reduce 45% emissions by 2030 and achieve net-zero by 2050. Initially these commitments were focused on Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, which are produced by the companies directly or through the purchase of energy. However today, most companies have pledged to reduce their Scope 3 emissions generated in the upstream and downstream value chain. This is a crucial step since, for many companies, Scope 3 accounts for 80% of their overall climate impact.

Given the scale of the problem, it is imperative to set ambitious targets and implement a well thought approach to deliver on them. Achieving net-zero for Scope 1 and Scope 2 themselves requires overcoming formidable economic and technical challenges. Scope 3 presents an additional layer of complexity such as aligning internal stakeholders on goals and milestones; working collaboratively with supply chain partners, customers; keeping all partners engaged in multiyear change efforts; non-transparent carbon accounting and tracking mechanisms.

An in-depth assessment through in-person consultations with Textile & Apparel (T&A) stakeholders, which included industry leaders such as H&M, IKEA, Marks and Spencer and their manufacturing partners, and learning’s from our initiatives have identified key gaps that need to be addressed to develop the supply chain infrastructure for circular and net-zero apparel:

Hence Intellecap, through its initiative Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF), is working with upstream supply chain partners primarily SMEs to reduce carbon emissions, through testing, validating and commercial adoption of circular and low-carbon solutions in resource efficiency (energy, water), alternate materials (low-carbon dyeing alternatives, etc.), and from recovering value from waste (fiber2fiber recycling). Based on our learnings, we believe that four steps need to be followed by organizations that are committed to multiplying their own efforts and decarbonizing the supply chain through supplier engagement. They are:

Research findings have indicated that existing solutions which include renewable electricity, sustainable materials and processes, alternate fuels, etc., have the potential to reduce supply chain carbon emissions by 47%. However, for the balance there is a need to test, validate and adopt innovative technologies and business models such as next generation materials, waterless dyeing, dry processing just to name a few. In order to address this, through our ongoing initiatives we have successfully worked towards building a strong business case for low carbon / circular supply chain solutions available in India. Project ACE, a two-year program (2021-2023), designed as a common action platform with the singular purpose of establishing a business case (economic value creation for the private sector organizations while reducing their environmental footprint). To create a robust business case, CAIF designed demonstration pilots with multiple stakeholders (brands and their manufacturing partners) to test, validate and commercially deploy high potential low-carbon solutions in areas including energy efficiency, water efficiency, alternative dyes and chemicals, digital solutions in textiles waste traceability, etc.

In the last 12 months alone, we have undertaken six pilots and delivered the below outcomes:

According to our private sector partners, three key aspects were critical in design /execution of the pilots along with expediting the buy-in from leadership / board teams for eventual long-term commercial contracts:

Hence based on these learnings we believe there is a need for and are working towards designing long term transformation programs with brands and their supplier networks to lay the foundation of a circular supply chain infrastructure and catalyze their journey to NetZero.

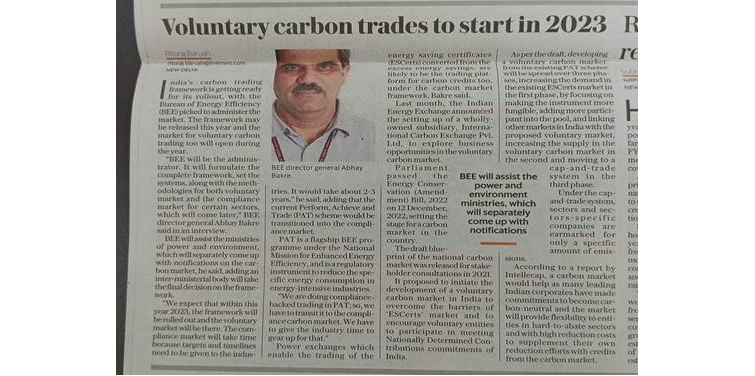

Voluntary carbon trades to start in 2023 -Intellecap report featured in Mint

Mumbai 24th Jan– Mint’s story (Print and Online) titled ‘Voluntary Carbon trades to start in 2023’ featured the Intellecap report on carbon markets and highlighted the India’s carbon trading framework with details from Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) with whom the Intellecap Climate team works extensively.

India’s carbon trading framework is getting ready for its rollout, with the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE) picked to administer the market. The framework may be released this year and the market for voluntary carbon trading too will open during the year.

“BEE will be the administrator. It will formulate the complete framework, set the systems, along with the methodologies for both voluntary market and the compliance market for certain sectors, which will come later,” BEE director general Abhay Bakre said in an interview.

BEE will assist the ministries of power and environment, which will separately come up with notifications on the carbon market, he said, adding an inter-ministerial body will take the final decision on the framework.

“We expect that within this year 2023, the framework will be rolled out and the voluntary market will be there. The compliance market will take time because targets and timelines need to be given to the industries. It would take about 2-3 years,” he said, adding that the current Perform, Achieve and Trade (PAT) scheme would be transitioned into the compliance market.

PAT is a flagship BEE programme under the National Mission for Enhanced Energy Efficiency, and is a regulatory instrument to reduce the specific energy consumption in energy-intensive industries.

“We are doing compliance-backed trading in PAT; so, we have to transit it to the compliance carbon market. We have to give the industry time to gear up for that.”

Power exchanges which enable the trading of the energy saving certificates (ESCerts) converted from the excess energy savings, are likely to be the trading platform for carbon credits too, under the carbon market framework, Bakre said.

Last month, the Indian Energy Exchange announced the setting up of a wholly-owned subsidiary, International Carbon Exchange Pvt. Ltd, to explore business opportunities in the voluntary carbon market.

Parliament passed the Energy Conservation (Amendment) Bill, 2022 on 12 December 2022, setting the stage for a carbon market in the country.

The draft blueprint of the national carbon market was released for stakeholder consultations in 2021. It proposed to initiate the development of a voluntary carbon market in India to overcome the barriers of ‘ESCerts’ market and to encourage voluntary entities to participate in meeting Nationally Determined Contributions commitments of India.

As per the draft, developing a voluntary carbon market from the existing PAT scheme will be spread over three phases, increasing the demand in the existing ESCerts market in the first phase, by focusing on making the instrument more fungible, adding more participant into the pool, and linking other markets in India with the proposed voluntary market, increasing the supply in the voluntary carbon market in the second and moving to a cap-and-trade system in the third phase. Under the cap-and-trade system, sectors and sectors-specific companies are earmarked for only a specific amount of emissions.

According to a report by Intellecap, a carbon market would help as many leading Indian corporates have made commitments to become carbon-neutral and the market will provide flexibility to entities in hard-to-abate sectors and with high reduction costs to supplement their own reduction efforts with credits from the carbon market.

The market would incentivize entities with low reduction costs to reduce emissions beyond their mandate. Trading in the carbon market could reduce the overall cost of emission reductions in India, it said.

Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group joins the Sustainability Task Force as part of G20 India Presidency

Mumbai, 23rd Jan: Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group has joined the sustainability task force as part of the new engagement group StartUp20, initiated under India’s presidency of G20.

The Inception Meeting for #Startup20 marks the beginning of an incredible journey to foster innovation and growth in the global startup ecosystem. At this historic event, we will be introducing the 3 task forces that will drive the vision and mission of Startup20 India

One of the key ways that startups promote a nation’s growth and economic stability is through the aspect of employment creation. Startup20 is a significant step in the direction of encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship on a global scale, which will ultimately result in more job opportunities.

Startup20 Inception Meeting – Hyderabad

Date – 28 – 29 January 2023

To know more – Click Here

Reports & Policies

Our Impact Map

Sign up for our newsletter

© Copyright 2018 Intellecap Advisory Services Pvt. Ltd. - All Rights Reserved