-

BusinessIndia

| November, 03, 2021The Textile & Apparel sector looks to build capabilities to drive the transition to a circular economy – Coverage of CAIF in Business India’s Special Edition Nov Issue 2021

Read More -

BWDisrupt

| October, 31, 2021Closing the Loop on Plastic Waste in India’s Textile and Apparel Industry

Read More -

The Economic Times

| October, 12, 2021New banking laws required for microfinance to take root, says Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus

Read More -

Nextbillion

| September, 17, 2021From Local Manufacturing to Digital Tech: How African Organizations are Pivoting to Support Maternal and Child Health During COVID-19

Read More -

Financial Express

| September, 15, 2021Fighting Fever outbreak in Firozabad, UP and ill-prepared health systems: Need for multi- level approach

Read More -

Pro MFG Media

| September, 09, 2021Doing Well by Doing Good: Building a Circular Textile Industry must be a Collective Effort

Read More -

BWDISRUPT

| August, 18, 2021Breaking Innovations in the Clean Technology Sector in India – Article by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Read More -

BWDisrupt

| August, 10, 2021Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative – Article by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Read More -

ET Energyworld.com

| August, 04, 2021Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive advisor: Mitsui invests in PRESPL- India’s Leading Biomass Supply-Chain Management Company.

Read More -

VC World

| July, 17, 2021Off-Grid Solar Refrigeration: Cure to the Growing Vaccine Wastage Crisis – Article by Ankit Gupta and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in VC World

Read More - Conduct knowledge sharing sessions to highlight benefit of solar refrigerators over diesel and other technologies especially based on lifecycle costing.

- Establish a digital platform with data on technology applications and potential market segments to enhance knowledge about off-grid solar refrigerators.

- Empanel solar companies providing off-grid solar refrigerators through a bi-annual selection process to enable quick deployment of technology.

- Provide disincentives to health care centres for usage of diesel generators in favour of solar technologies (like off-grid solar refrigerators and solar PV systems).

- Provide a dedicated budget for implementation of DRE systems at health care centres through the existing national/state level policies.

- Aggregate financial assistance at the national/state level through external funds from development agencies, CSR funds, private foundations etc.

- Deploy/use innovations like blockchain to provide real-time visibility of vaccine distribution from manufacturing to administration and eliminate supply chain gaps.

The Textile & Apparel sector looks to build capabilities to drive the transition to a circular economy – Coverage of CAIF in Business India’s Special Edition Nov Issue 2021

Mumbai, 5th November– Recently Circular Apparel Innovation Factory got an extensive 3 page coverage titled, ‘The Textile & Apparel sector looks to build capabilities to drive the transition to a circular economy’ by Assistant Edito Arbind Gupta, Assistant Editor, Business India, for their Special Edition, November Issue.

This is now available both Online and on Print.

The textile and apparel (T&A) manufacturing is considered to be one of the most polluting industries. In fact, the T&A industry is the second most polluter globally. Over 20 per cent of industrial water pollution occurs due to garment manufacturing. Globally, 80 per cent of textile waste generated is not recycled and often sent to landfills or incinerated. In fact, the industry is responsible for polluting over 8 per cent of global climate. With growing economy and changing demographics, the consumption of textiles and clothing has gone up by more than 60 per cent today as compared to that in 2000 and this has significantly aggravated the whole situation. In the past 15 years, the textiles production has almost doubled.

Amidst all this, the industry is finding itself in a quandary as it is struggling to balance between its mainstream targets of productivity & production and the sustainability goals. The current linear system of production, distribution and usage of T&A is not sustainable as there is less regard for environment impact. Experts are of the view that the current `take-make-dispose’ approach does not only adversely impact the environment and society, but also the future business of the T&A industry.

While there are a few sporadic interventions across the value chain happening in order to address the issues and making the value chain more sustainable, the concerted effort is missing. In order to deal with these issues in a more holistic manner as also set the goals and achieve them in a time-bound manner, an industry-led platform – Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF) – has been put in place recently in India. Started in 2018 and formally launched in November 2019 at Sankalp Forum’s 11th Global Forum in Mumbai, CAIF is a global initiative of Intellecap, the impact advisory arm of the leading impact investing organisation, the Mumbai-headquartered Aavishkaar Group, which works to build businesses that can benefit the underserved segments across Asia and Africa. Intellecap builds enabling ecosystems and channel capital to create and nurture a sustainable and equitable society.

CAIF is supported by the DOEN Foundation, a Dutch foundation supporting initiatives in the field of culture and cohesion and in the field of green and inclusive economy, as also Aditya Birla Fashion & Retail Ltd (ABFRL) as its founding anchor partners. To accelerate the shift of the industry from its current ‘take-make-dispose’ approach to one that is more circular across the lifecycle, CAIF works with a diverse group of stakeholders from across the value chain.

Circular goals

“As an industry-led platform, CAIF’s mission is to build the ecosystem and strengthen capabilities to drive the transition to a circular economy in the apparel and textile industry. The platform is building the textile industry’s innovation infrastructure by bringing together key stakeholders to collaborate and work together on achieving the five key circular goals: increasing the use of sustainable inputs and material; maximising the utilisation of clothing & textiles; increasing the recycling of clothing; boosting production through renewable inputs; and minimising negative social impacts and increasing social responsibility,” says Venkat Kotamaraju, director, CAIF.

“We are pleased to partner with Intellecap to accelerate sustainable fashion concept through CAIF and build an industry level platform for a circular textile ecosystem. We intend to bring forth ideas and innovations to add more strength to our pioneering work around sustainability. The association with Intellecap will help us create, collaborate and mainstream the conversation around circular economy and sustainable fashion,” states Ashish Dikshit, managing director, Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail Ltd.

The industry lacks an infrastructure to deal with textile waste

The industry-led body has over the years, partnered with a host of like-minded organisations with whom it is building a body of work spanning the ecosystem. For example helping identify the key circularity levers and mapping them against policy interventions that needed design (a policy-led programme in partnership with Centre for Responsible Business) and building a body of evidence on how designing for inclusion into circular business models can help deliver both ecological and social outcomes (a collaboration with Netherlands-based The Laudes Foundation).

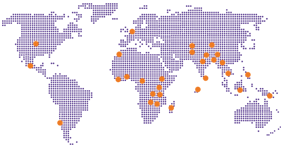

Over the last three years, CAIF has been actively working with over 15 Indian and global brands through different pilots and initiatives, and has identified and mapped over 400 innovators across different dimensions of circular economy relevant to the textile and fashion industry. CAIF aims to have 50 to 60 partners in India and globally in the next 2-3 years and expand its presence beyond India and Bangladesh to others parts of the world especially global south economies like South Asia, like Sri Lanka and Nepal; East African countries like Kenya, Tanzania and Ethiopia and South East Asian countries like Indonesia and Vietnam.

The T&A platform is targeting these regions because they are critical from the global value chain in the fashion industry. They are critical since global south accounts for a significant amount of manufacturing for the global value chain of the global industry. For example, India is one of the biggest importers of textile waste from the US and the Europe. The country recycles it and sends it back. Besides, more than 50 per cent consumption of fashion and apparel is in global south. Global South is economies outside the developed economies like the US and the Europe.

“With the global south economies being significant contributors to sourcing, manufacturing, exports, recycling and consumption, in the complex global value chain, it was crucial for the global south to have a voice and a seat at the table. While there was growing momentum globally (especially in Europe) from individual organisations, we saw an opportunity in taking an ecosystem approach that will not just surface the dots (gaps and stalemates) but also help connect the dots (mobilising capital, knowledge and networks to build the ecosystem) in interesting ways for impact to happen at scale. More importantly, while the dominant narrative globally around circular economy emphasises economic and ecological value creation, CAIF aims to alter this narrative that also includes how we ensure no individual or group is left behind on this path towards progress,” explains Kotamaraju.

Kotamaraju: building the ecosystem

Kotamaraju: building the ecosystemCAIF is looking to make the work of the apparel, textile and the fashion industry more sustainable (resource efficient, resilient and responsible) through reducing carbon emissions (both avoidance and removal), while creating green and circular jobs for those employed across the value chain. Some of the partner brands and manufacturers have very clear and ambitious targets like for e.g. moving to recycled water usage (away from fresh water) by 70-100 per cent between 2025 and 2030, eliminating energy usage and consumption by 30-50 per cent by 2030, replacing virgin material usage with recycled material use by 50-70 per cent by 2030 etc.

World changing companies

In the last three months, the industry platform has created a showcase of circular innovations and sustainable innovations to at least 60 suppliers of the top 3 brands and manufacturers. In fact, it has recently entered into partnership with IKEA Foundation along with Enviu (the Netherlands-based social organisation that together with partners, builds world-changing companies that address social and environmental issues) to support innovative interventions that are designed to not just deliver on environmental outcomes but also help create green livelihoods. Through this partnership, CAIF is looking to build a circular textile waste management model in the next five years. The IKEA Foundation is funding the initial and seeding phase of the five-year project, which will be implemented as a joint initiative of Enviu and CAIF.

In the next five years, the programme aims to deliver on clear outcomes, one, on environmental outcomes, it is looking to divert 20 million kg of textile waste away from the landfill and help recycle them and find its way back into the value chain. By recycling it and reclaiming value from the textile waste, the project is reducing the dependence on natural resources by replacing some amount of virgin material with recycled materials. Through this programme, CAIF is looking to create at least 5,000 new green jobs for base workers. In the first phase of this ambitious programme, Enviu and CAIF will be seeking partnerships with manufacturers, brands and innovators to scale and replicate solutions to manage textiles waste; as well as NGOs and other civil society actors to build skills and capacities amongst the waste workers in India.

Creating better livelihoods

“The IKEA Foundation has always worked towards supporting people living in underserved communities to afford a better life. There is huge potential in the textile waste sector not only to become more sustainable but also to create better livelihoods for a large number of people at the bottom of the pyramid. We believe that green and circular entrepreneurship in India’s textile waste sector offers an opportunity for vulnerable workers to lift themselves out of poverty while protecting the planet. That’s why we are happy to be part of this initiative,” says Vivek Singh, Head of Portfolio – Employment and Entrepreneurship, IKEA Foundation.

Avers Ankie Van Wersch, CEO, Enviu, “We believe building impact-driven companies that prove and showcase it is possible is key to achieving a new normal: a textile industry that serves people and planet. Enviu’s top-down impact-driven venture building approach, combined with CAIF’s bottom-up ecosystem building amongst waste workers is a winning combination, maximizing impact. We look at the obstacles to change in the textile industry and fill in the gaps with new ventures, while CAIF starts from the capabilities of the waste workers. The ventures we build create income for the waste workers. I have seen the impact our circular ventures create on families first-hand.”

Textile and apparel manufacturing is considered second most polluter globally

It may be noted that India is one of the world’s largest textile producers and importers of used clothing, but lacks an infrastructure to deal with textile waste, leaving an estimated 4 million informal waste workers trapped in low-income, unreliable jobs. Enviu and CAIF, together, will build capacities and skills amongst these waste workers, and build successful circular enterprises to reclaim value from textile waste. This will reduce the environmental impact of the clothing industry while enabling the workers to increase their incomes and afford a better life. India is the one of the largest employers of workforce in textile and apparel, only next to the agriculture sector.

CAIF has also been partnering with Lakme Fashion Week for the last two years to co-create and develop two initiatives – Circular Design Challenge and Circular Changemakers. It firmly believes that a credible dent on any of the 2030 SDGs isn’t possible without the role of the private sector. Through the body of work so far and a host of interested and willing partners, the industry body is already shaping work beyond just India.

In Bangladesh, it is building local and indigenous capacity within the apparel manufacturing sector for recycling of blended textiles waste (collection, sorting and recycling) and establishing an ethical and traceable collection mechanism for PET collection and recycling which is free of child-labour. In Sri Lanka, the communities living around and dependent on oceans, play a crucial role in designing programmes that look at how brands and manufacturers can help provide these underserved individuals and communities access to safe drinking water and sanitation, while restoring ocean biodiversity. Such an intervention is anchored in the community working towards zero leakage of textiles and plastics waste into the oceans through responsible and resource efficient collection, sorting and recycling solutions that create economic value for the underserved communities in the mid to long term.

All in all, CAIF’s efforts range from helping decarbonising the textiles and apparel supply chain in the global south, to getting to zero leakage of waste into the environment (from textiles, plastics, agriculture or forest products) while creating circular and green jobs in the manufacturing, recycling and the innovation ecosystems.

Closing the Loop on Plastic Waste in India’s Textile and Apparel Industry

Mumbai, 1st November– The Article, ‘Closing the Loop on Plastic Waste in India’s Textile and Apparel Industry’ by Siddharth Lulla, Lead Corporate Strategy and Enterprise Engagement, Circular Apparel Innovation Factory talks about how due to weak enforcement and the continuing popularity of plastic packaging among retailers and consumers in the absence of any suitable alternative, the country has not been able to achieve substantial success in reducing the usage of plastics.

This article, was the 5th one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with the Business World Group.

India’s plastic consumption has grown significantly over the last decade. As per industry estimates India consumes c. 16 million tonnes of plastic on an annual basis, contributing to generation of c. 9.47 million tonnes of plastic waste annually. Only 60% of the total waste generated is processed while the remaining is unsegregated, littered and ends up in landfills or the natural environment.

Around 43% of manufactured plastic is used for packaging purposes, majority of which is Single Use plastic i.e. used only once and disposed. While plastic packaging plays a key role of protection, marketing and advertising, the complete lifecycle of this is not thought through, resulting is substantial waste generation.

India’s textile and apparel (T&A) industry is one of the world’s largest, and is a major contributor to global textile and apparel production and consumption. The industry is estimated to be worth USD 190 billion by 2025-26.2 It currently employs more than 45 million people making it the second largest employer in India – contributing over 15% of the country’s export earnings, and almost 7% of the it’s industry output. Although the industry exhibits a positive trend in terms of growth on the back of an exponential rise in fashion retail and online shopping, it is a significant contributor to the Single Use plastic packaging waste generation.

Current Policy Landscape around Single Use Plastic in India

The Government of India has announced a number of steps to phase out and eventually completely stop Single Use plastics usage to reduce the country’s plastic footprint. The 2016 Plastic Waste Management Rules put curbs on use and generation of plastic packaging waste. This includes prohibition of carry bags made of virgin plastic less than 50 microns in thickness in order to facilitate ease of collection and recycling of plastic waste. Under the new rules the government now plans to ban bags less than 120 microns by next year.

Additionally regulations for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)4 have also been introduced, according to which the producers (manufacturers, importers and those using plastic in packaging) as well as brand owners would be held responsible for collecting the plastic waste they generate and ensure a minimum percentage of the produce is recycled or used in supply.5 The proposed EPR framework has provisions to impose penalties if producers fail to meet their targeted collection.

Due to weak enforcement and the continuing popularity of plastic packaging among retailers and consumers in the absence of any suitable alternative, the country has not been able to achieve substantial success in reducing the usage of plastics. However, a clear shift from regulatory intent to action is now visible. The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has sent notices to 52 companies for not registering and specifying their single use plastic disposal plans under the EPR framework.

It is therefore, imperative for the T&A industry to adopt a strategy aligned with the principles of the circular economy to address challenges posed by single-use plastics waste.

The concept of a single-use plastics free circular economy, which can harness the benefits of plastics while addressing its drawbacks, and deliver significantly better system-level economic and environmental outcomes, is gaining traction in India and the rest of South Asia. Transition to such a circular system therefore, involves keeping useful plastics in the economy but out of the environment. This will entail simultaneous progress on multiple fronts including a re-evaluation of the plastics lifecycle, new commercially viable circular business models, development of alternative materials, new technologies, better land-based and marine plastic waste management solutions, awareness generation and enabling policy interventions.

In order to do so, India must adopt an integrated approach to collecting, segregating and recycling plastic waste that would ensure adequate recovery and collection mechanisms enabling producers and manufacturers to recycle plastic waste through a plug and play model.

There is an emergence of Integrated closed loop solution providers which have a holistic goal of reducing the generation of single use plastic in the ecosystem by collecting the waste packaging material from business/ end consumers, recycling it and converting it back into usable products. Such solutions fundamentally address the habit of waste disposal rather than just replacing the material through programs or mechanisms to collect all the recycled plastic products from various distribution points in the chain.

In an initiative to demonstrate a business case of how the entire plastic waste generated by a fashion brand can be collected, recycled and prevented from going to the environment, the Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF), an initiative by Intellecap, facilitated a pilot project in October 2020 between House of Anita Dongre, a brand at the forefront of sustainability in India and Lucro Plastecycle Pvt Ltd, a Mumbai based enterprise which collects and develops packaging from recycled post-consumer plastic waste.

House of Anita Dongre currently has 1200 retail touch points across the country. The pilot when scaled will recycle c. 6 Million polybags on an annual basis and manage the entire plastic waste generated by House of Anita Dongre at a pan India level. CAIF will disseminate the learnings and insights on best practices from this initiative to the industry. As per Rohan Batra, (Head Sustainability & CSR, House of Anita Dongre) the partnership with Lucro and CAIF has been huge step in making the brand reduce its plastic footprint and bring in efforts to reduce the carbon footprint due to plastic waste generated so far. Rohan points out that the pilot has already been successful in introducing 6.5 lac polybags with 60-75% post-consumer recycled content in the supply chain. Since its inception the pilot has resulted in a monthly average of 500 kgs of plastic waste and 1.25 lac polybags being recycled at House of Anita Dongre resulting in a conservative 30% savings in carbon footprint.

Lucro also provides a blockchain enabled traceability tool called Satma CE, which validates the origin & supply chain process of the post-consumer waste used. Ujwal Desai, MD, Lucro Plastecycle Pvt Ltd mentions that Lucros trademarked Plast-E-Cycle process creates a circular economy for plastic, making the recycling and remanufacture of plastics more efficient and high quality. It definitely helps that Lucro is involved in every step of waste management, from collection and segregation, processing into granules, product design and manufacturing of high-quality, innovative and eco-friendly products.

The partnership between House of Anita Dongre, Lucro and CAIF demonstrates that integrated closed loop solutions are poised to create a cascading effect in India’s T&A industry. It is evident that with the right support, innovative solution providers are ready and willing to drive significant environmental and social impact both in the country as well as demonstrate circular models that can be scaled globally.

New banking laws required for microfinance to take root, says Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus

Noble laureate and founder of Grameen Bank Muhammad Yunus on Tuesday emphasised on the creation of a new law for banking to help microfinance reach unbanked people and encourage the creation of social businesses. He said that currently, there is one banking law that prescribes a number of regulations for banks, most importantly of having collateral for offering loans.

“The first thing that I have been repeating for many years is that in order for microfinance to take hold in business, you have to create a new law for banking.

“Today, there is only one law for banking called banking law which defines what a bank should be. The banking law means that you have to have collateral and other requirements,” Yunus said at the 13th Sanklap Global Summit 2021.

According to him, for having a bank for the poor, there is a need for creation of a new banking structure which is not based on collateral.

“We need a complete redesign of the financial system. And within the financial system, we have to build a social business financial system-social business bank, social business investment funds, social business microcredit banks, and so on,” Yunus noted.

He also raised concerns over concentration of wealth in the hands of very few people.

Yunus said this gap can be reduced if everyone becomes an entrepreneur.

Finance is the oxygen of entrepreneurship and one cannot have entrepreneurs without having connections with the financial set-up, he said.

“Why can’t we create a new financial system, so that everyone has a connection with it. If you have a connection with it, then you change yourself and you can have a share in the wealth,” he added.

From Local Manufacturing to Digital Tech: How African Organizations are Pivoting to Support Maternal and Child Health During COVID-19

Mumbai, 20 September – The article by Shraddha Kothari, Manager, Intellecap titled, ‘From Local Manufacturing to Digital Tech: How African Organizations are Pivoting to Support Maternal and Child Health During COVID-19’ was featured in Next Billion.

This article is part of NextBillion’s series “Recovery 2021,” which explores how businesses, development initiatives and the communities they serve in low- and middle-income countries are building greater resilience for a post-pandemic future.

Sub-Saharan Africa has witnessed a sustained improvement in maternal and child health outcomes in the last two decades. The maternal mortality ratio in the region has declined from 870 per 100,000 births in 2000 to 534 per 100,000 births in 2017. However, despite this impressive progress, the region still has the highest neonatal mortality rate in the world, with 27 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2019. It also accounts for over two-thirds of all maternal deaths worldwide.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has stressed global healthcare systems and reduced the availability of medical services across the board — and maternal, newborn and child health services are no exception. There has been a notable reduction in the utilization of these services in sub-Saharan Africa, as measures such as curfews and lockdowns have been used to curb the spread of the pandemic across the region, affecting how women seek and access health facilities in these countries.

In Liberia, for instance, the number of women who attended the recommended medical visits during pregnancy dropped by 18%, while the number of women seeking to initiate medical care during pregnancy fell by 16% in Nigeria. In Uganda, a study found that women’s attendance at antenatal services dropped by 26%. In addition, the study also noted a rise in: adverse pregnancy outcomes for Caesarean sections (5%), haemorrhages related to pregnancy (51%), stillbirths (31%), low-birth-weight (162%) and premature infant births (400%). Similarly, in Ethiopia the pandemic affected the utilization of reproductive, maternal and newborn healthcare services, worsening both maternal and perinatal outcomes.

This has, unfortunately, led to a further increase in maternal mortality in various African countries. Consequently, it is imperative to recalibrate and scale models that can prevent the further deterioration of maternal and child outcomes in the region’s already-strained healthcare systems. There have been some organizations that have done just that, benefitting from a reduction in their immediate supply chain vulnerability and also attaining long-term economic and environmental benefits. Below, we’ll explore a few of these organizations’ pandemic responses, and discuss what other healthcare providers can learn from them.

DEVELOPING LOCAL MANUFACTURING TO OVERCOME SUPPLY CHAIN CHALLENGES

The Safe Motherhood Alliance, a for-profit social enterprise in Zambia, sells low-cost delivery kits to expectant mothers for a safer birth experience. As a result of the pandemic’s disruptions in the global supply chain, the enterprise pivoted its model and commenced manufacturing the products that it was struggling to source through its usual suppliers. It has developed the local manufacturing capacity to produce some of the items — such as sanitary napkins and face masks — that were needed for its delivery kits. Moreover, it has leveraged locally available materials, like the fibres of banana skins, to make sanitary napkins, allowing it to produce them at a fraction of the cost of importing them.

When the Safe Motherhood Alliance reaches full production, it will be able to sell these sanitary napkins to other relevant groups, such as adolescent girls. Overall, leveraging local manufacturing and available materials will not only enable the enterprise to support safer births at a lower cost, but it will also allow it to expand its customer base.

ADAPTING TECH-BASED MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH SOLUTIONS

In recent years, organizations have deployed several technology-based solutions to support improved health outcomes for maternal and child health in sub-Saharan Africa. As a result of the pandemic, some of these health-focused organizations have refined their models and formulated partnerships to support expectant mothers. For instance, Child.org, an NGO in Kenya that focuses on improving global child health partnered with MamaTips, a non-profit maternal health organization that has developed a mobile subscription service. The partnership enables Child.org to provide essential information to expectant mothers via SMS texts, in the absence of the face-to-face meetings that were a part of its delivery mechanism. Such partnerships can be effective in scaling existing programs focused on maternal and child well-being, even beyond the pandemic.

Another digital platform, MomCare, increased its offerings to expectant mothers during the pandemic. It provided women in Kenya with details on facilities that could be accessed despite the curfew, and also connected them to transport services so they could access these facilities. MomCare’s mobile phone-based application enables the staff at healthcare facilities to track the progress of expectant mothers digitally and in real-time.

Similarly, in Nigeria, the digital health enterprise mDoc expanded its scope of services to meet the pandemic-fueled increase in demand for digital health services by expectant mothers. This for-profit enterprise hired more coaches and deepened the support offered to these women. Given the limited access to health care facilities, the enterprise refined its curriculum and modified its processes to provide these expectant mothers with further guidance on clinical care and support to manage pregnancy-related health issues like high blood pressure.

These examples demonstrate that there is significant potential to leverage and integrate technology-based health solutions in the region — not only to provide care during the pandemic but also to improve and scale existing health service delivery and support services for expectant mothers.

COVID-19 has already worsened maternal and child health outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. As the crisis gradually abates it will be critical to evaluate, adapt and scale health service delivery models and support service programs to prevent — and ideally, reverse — any further loss of the previous gains made in maternal and child health outcomes across the region.

Fighting Fever outbreak in Firozabad, UP and ill-prepared health systems: Need for multi- level approach

Mumbai, 15 September – The Author, Sagar Atre from Intellecap uses his previous work experiences in fostering health innovations in the domain of infectious diseases, to talk about a recent outbreak through this article.

Sagar’s article, which was covered by Financial Express titled, Fighting Fever outbreak in Firozabad, UP and Ill preperaed health systems: Need for multi level approach is pertinent given the recent outbreak and gives us a sense of the hinterlands of India, where unsanitary conditions, poor preventive behaviours and a lack of surveillance mechanisms make it a breeding ground for many diseases.

In a recent article, Dr. Raj Panjabi, a noted public health professional and the head of the U.S President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) wrote, “Alarm bells don’t ring in health crises, community workers do.” This is especially true in the hinterlands of India, where unsanitary conditions, poor preventive behaviours, and a lack of surveillance mechanisms make it a breeding ground for many diseases.

The unfolding crisis in Firozabad, Uttar Pradesh is an example of what such micro health crises can do if we don’t work towards enhancing our public health capabilities. Similar crises have occurred in 2015 and 2019, where outbreaks of similar fevers were attributed to dengue and scrub typhus. U.P. ‘s Bareilly has been one of the few urban areas to report a spike in malaria cases, reporting up to 20,000 cases in a span of weeks in 2019, at a time when malaria is nearly non-existent across much of India barring a few scant pockets.

Battling old scourges

Diseases such as malaria, dengue, scrub typhus, and leptospirosis are remarkably good indicators of glaring gaps in health systems. They can lay bare the hollow claims of policymakers by bringing health systems to their knees and giving doctors barely any time to respond. A lack of discipline in implementing prevention programs can lead to spectacular failures such as the one in Firozabad, where according to recent figures, around 5000 people are suffering from symptoms similar to dengue, while more than 100 confirmed deaths have occurred in Firozabad and other districts in Western UP.

Dengue fever is easy to ignore in usual public health systems. It causes mild illness in many people, but can prove to be fatal for the young and healthy with supposedly strong immune systems and wreak havoc among children. Aedes mosquitoes are suited to breed in cleaner water, in small water collections such as water coolers, among others and they bite mostly during the day, making bed nets and ointments redundant.

Another threat is scrub typhus, caused by a bacterium (O. tsutsugamushi) and spread through bites of small insects called larval mites which dwell in dry scrubs and bushes near the fields in rural areas, where children often play and many of those practicing open defecation need to go. Unlike Dengue and Malaria, scrub typhus has remained largely off the radar, and no real estimates can be gleaned from public health data. The third purported culprit of this outbreak is leptospirosis, usually contracted through contaminated water, soil or food. While scientific evaluations are unavailable, the Delhi government’s effort at making Sunday a day of clearing stagnant water in domestic settings was a doable task for most households.

Ill-prepared health systems

Most of India, especially the rural and semi-urban parts are ill-prepared to deal with most of these diseases. Most labs in such places struggle to perform tests which can differentially diagnose these ailments. The international pressure to control malaria helped the discovery of rapid diagnostic kits, but others such as dengue, scrub typhus, leptospirosis remain undiagnosed, or need a skilled diagnostician. Investments that are needed are often missing, and that means that most of the tests performed for diagnosing diseases remain inaccurate. While multiple forms of dengue tests are available, the RTPCR remains the most reliable. Tests for scrub typhus and leptospirosis remain unreliable and it is unlikely that they will be performed even in district hospitals in the country due to the facilities required. In sum, India’s In sum, India’s scientific efforts need to be directed towards developing tests which can help in diagnosing these diseases, or at least providing a provisional diagnosis for them.

The need for multi-level approaches

The key challenge remains the lack of a holistic thought process for tackling the challenge at multiple levels. Impact of infectious diseases on public health can be dealt with at four key levels. Primarily, it is our inability to implement basic practices of hygiene, sanitation and build strong primary health systems. The second issue is identifying and building strategies and strategic capabilities specific to India’s regions. The third is a lack of focus on developing innovative solutions which can tackle these health challenges through the country’s growing scientific capabilities as was done for COVID-19. Many of India’s institutions such as BIRAC, the DST, the IISc, IISER’s and IIT’s are now proving to be useful in creating innovative solutions for diagnosis and management. They need to be given the mandate of building solutions to tackle them. The final, and probably most complicated challenge is designing interventions which inculcate appropriate health behaviours and improve uptake of health services by the community. Many NGOs and institutions across India have been at the forefront of designing such initiatives across challenging geographies in India.

It would probably be appropriate to say that for India, apart from the fundamental capabilities to ring the alarm bells, we also need the capabilities to nimbly tackle the cause of the alarm, and prevent such incidents in the future.

Doing Well by Doing Good: Building a Circular Textile Industry must be a Collective Effort

Mumbai, 9 September – Currently, the textile industry is estimated to be worth USD 103.4 billion and is expected to grow up to USD 190 billion by the year 2025-2026.

As part of the Pro MFG Sustainable Circular Economy Series – Doing Well by Doing Good, powered by BiofuelCircle, Siddharth Lulla, Lead – Corporate Strategy for Circular Apparel Innovation Factory (CAIF), Intellecap, shares key insights on the need for stakeholders to come together towards bringing about circularity in the textile industry.

The Indian textile and apparel industry is one of the world’s largest, and is a major contributor to global textile and apparel production. Currently, the industry is estimated to be worth USD 103.4 billion and is expected to grow up to USD 190 billion by the year 2025-2026. Today, the Indian textile industry employs more than 45 million people, making it the second largest employer in India. It contributes to over 15 percent of the country’s export earnings, and almost 7 percent of the country’s industrial output (India Brand Equity Foundation, 2018).

Although the industry exhibits a positive trend in terms of growth, the question of sustainability looms large. The Indian textile and apparel industry has two broad issues related to sustainability. First, it is one the most polluting industries in the world. Secondly, it is plagued by social inequities.

More than 80% of textile waste generated is sent to landfills or incinerated instead of being recycled or reprocessed. At the same time, India is increasingly facing the pressure to match supply and demand due to resource constraints in core areas like cotton production. There is, therefore, a critical need to ‘self-disrupt’ existing practices and transition towards pathways, and Circular Economy (CE) is the ideal model to be followed.

Aligning with the principles of the CE entails adopting a more strategic and future-oriented mindset to the entire lifecycle of products from material production, manufacturing, use, and closing the loop on waste. A CE is an emerging phenomenon with the potential to completely change the textile & apparel system.

Products in such a system are designed to be used more; made to be made again and made from safe and recycled or renewable inputs. While prioritizing the rights and equity of everyone involved are not highlighted in the CE literature, this is another critical area that needs attention in the journey to ‘going circular’.

The need for transformational leadership

Companies and manufacturers at the forefront need to lead this transformation. With increasing awareness of environmental and social issues, global brands have started implementing sustainable strategies, which include adoption of sustainable materials, reduced use and wastage of resources across the manufacturing process, etc.

On the other hand, individual designers, small companies and grassroot initiatives are demonstrating alternative ways to more sustainable businesses. There exist several examples of how to design, manufacture and do business in the context of the circular economy, the scaled adoption of which would need a systemic perspective and collaboration between different stakeholders, i.e, designers, producers, manufacturers, suppliers, business owners and even the consumers. This, in turn, would lead to new perspectives and networks that open different business and design opportunities.

Key challenges involved

The transition to a circular economy clearly requires significant changes in both production and consumption models. Some of the factors that impede stakeholders in this transition include:

● Lack of knowledge, awareness of the range of solutions and best practices, capabilities to deliver circular business models that can seamlessly integrate with current systems

● Risks associated with adopting circular solutions and models such as technology risk, high capital investments, high transition costs in order to switch to new solutions

● Capturing value requires both recyclability and durability. Refurbishing products can be an expensive process, if done reliably. Similarly, most garments are composed of a mix of materials (e.g. cotton, viscose, polyester), which makes recycling difficult

– Enabling circularity involves a complex and expensive network of logistics both in terms of collection and recycling waste (textile, apparel, packaging, etc.) establishing customer-facing retail models like rental, e-commerce, subscription, etc.

● Consumers too, are required to overcome stigmas in using upcycled, repaired and refurbished products

● Lack of reskilling and up-skilling initiatives to make workers future ready

Given these risks, despite a rise of innovation by new startups/ innovators leveraging technologies and processes to create sustainable solutions, a very limited number of them have been able to scale and thereafter mainstream their solutions.

There is a need to work collaboratively so as to bridge the gap between innovators and manufacturers to promote large-scale uptake of green solutions, not only by leading brands and manufacturers but also by small and medium enterprises to move towards sustainable practices.

Given the fragmented nature of the industry, standardized solutions are unlikely to emerge anytime soon. Hence, we are more likely to see a diverse range of strategies centered around the following fundamentals:

1. Embracing sustainable design:

● Train and reskill design teams on the principles of circular design

● Invest in, incubate and experiment with alternative materials and fibers

● Reduce leakage in the system by concentrating on material recovery at both a pre and post consumer level

● Develop efficient supply chains with reduced demand of resources (energy, water) and packaging

2. Optimize waste-to-value processes:

● Adopt new technologies and solutions that use waste to manufacture new input materials such as fibers and yarns.

● Adopt innovative solutions to optimize sorting and recycling technologies.

● Partner with logistics partners and solution providers to collect and recycle waste (textile, plastics) generated in the supply chain.

● Develop collection points and home pick-ups to improve accessibility.

● Eliminate single-use packaging by using sustainable / recycled alternatives.

3. Drive Customer Adoption:

● Project sustainability and circular practices at the center of branding decisions

● Offer alternative business models such as rental and subscription

● Provide traceability information about the products to build customer awareness and buy-in

● Enable strategies and systems to encourage returns and recycling

● Use data analytics and tools to help customers make informed decisions and reduce waste

Given the ambitious sustainability goals set by brands globally, circularity is likely to be one of the key business trends of the next decade. The onus is on global brands to encourage action and behavioral change of their suppliers and customers. Today, more than ever, a collective effort of brands, the government and consumers is required to scale circularity in the textile industry, which is the key to a more sustainable future.

Breaking Innovations in the Clean Technology Sector in India – Article by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Mumbai, 23rd August – The article in BusinessWorld Disrupt titled, ‘Pathbreaking Innovation in the Clean Technology Sector in India’ authored by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap, was the 3rd one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with the Business World Group.

According to the Central Electricity Authority, as of May 2021, the share of renewable energy in India’s total installed capacity (383.3 GW) stands at around 25% (95.6 GW). However, in power generation, it accounts for only about 12% at 14.13 billion units (BU) against a total generation of 118.09 Bus

The article sheds light on how we can transition towards a clean and green economy with an ecosystem-based approach.

India is at the cusp of its energy transition journey driven by the 3D concept – Decarbonization, Decentralisation, and Digitization. Even as large-scale renewable energy is rapidly making strides towards cleaning and greening the grid, fossil fuel-based polluting power generation continues to dominate India’s energy mix. According to the Central Electricity Authority, as of May 2021, the share of renewable energy in India’s total installed capacity (383.3 GW) stands at around 25% (95.6 GW). However, in power generation, it accounts for only about 12% at 14.13 billion units (BU) against a total generation of 118.09 BUs. Despite the growing share of renewable energy in the power basket of India, the challenge of providing clean energy to the on-grid and off-grid consumers still looms large. On the occasion of World Renewable Energy Day, Intellecap explores the mega-trends in the clean energy and climate change space in India highlighting key technologies within India’s 3D energy transition concept that promise a cleaner, more efficient, and resilient energy sector.

Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen has recently gained traction as one of the fuels of the future. The term green is applied to the hydrogen production process when it is produced using renewable energy. The adoption of green hydrogen has the potential to decarbonize sectors with significant carbon emissions. It can be applied in the chemical and fertilizer industry for the production of ammonia and methanol, the steel industry as a reducing agent, commercial and residential heat production, power generation, and fuel for transportation. Currently, the country utilizes around six million metric tonnes of hydrogen. This demand is expected to rise to 11 million metric tonnes by 2029-30. Production of hydrogen of this magnitude can lead to large amounts of carbon emissions which can be avoided by promoting and scaling up green hydrogen.

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has recently published the draft ‘National Hydrogen Energy Mission’ aimed at creating a green hydrogen value-chain, reducing production costs and phasing away from grey hydrogen (hydrogen produced from fossil fuels). The estimated cost of producing green hydrogen ranges from $3.6-5.8 per kg which is almost three times the cost of grey hydrogen. The recent indication from the government towards setting green hydrogen consumption obligations for the petroleum refining and fertilizer industry has led to traction from private sector and government players likewise. Notable examples include: Reliance Industries launched the India H2 Alliance (IH2A) to build the hydrogen economy; NTPC signed a MoU with Siemens for green hydrogen production from its RE plants; the Indian Oil Corporation plans to establish a green hydrogen plant to replace fossil fuels at its refinery; and Adani Enterprises is collaborating with Maire Technimont to implement green hydrogen projects.

Peer-to-peer Energy Trading through Blockchain

In the era of prosumers (consumers who produce their own electricity) peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading presents a viable solution to allow access to solar power for consumers with inadequate rooftop space or capital to set up solar power projects. Per this technology, excess energy from the solar rooftop plant of

a consumer can be sold to its neighbors. P2P trading uses blockchain technology to ensure transparent and reliable transactions. The transactions are carried out through smart contracts that can divert a pre-determined portion of energy to a consumer at a definite time, thereby encouraging decentralization and reducing the role of distribution companies and retailers. At present, the technology is only in the pilot stage and may take a few years to achieve universal acceptance. Significant resistance is expected from DISCOMs who may not like to see their high paying customers switch to energy trading. Moreover, the development of this infrastructure within high-density areas with limited rooftop space may not be financially viable.

India has already begun experimenting with P2P energy trading. BSES Rajdhani, in collaboration with blockchain technology provider Power Ledger, Australia, has created a solar oasis in Delhi’s grid-connected residential hub of Dwarka. The pilot project comprises 300 kW of solar power plants which services a group of gated communities. During the trial, residents with rooftop solar infrastructure were able to trade a total of 25 MWh of energy with their neighbors as well as with higher tariff commercial customers, minimizing the amount of energy that was spilled back to the grid.

Vehicle-to-Grid

Electric Vehicles (EVs) can use their batteries as decentralized storage systems for excess power when not in use, which can be fed into the grid through the vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology. EVs charged through solar-powered charging stations when combined together can integrate a considerable amount of renewable energy into the grid to help balance the load during peak hours. EV owners can be compensated in the form of direct payment per unit fed into the grid or through preferential EV charging tariffs. This bi-directional flow of energy can be especially useful when utilizing the time-of-day concept – EVs can use solar power to charge during the day and feed it back to the grid during the night. However, unless EVs scale up to the point where large amounts of energy can be stored in the batteries, V2G technology will remain a distant dream. Moreover, given the payment track record of cash-strapped DISCOMs, feeding energy into the grid may lead to financial turbulence for both the DISCOMs and the EV owners.

So far, research projects are underway in India to establish a proof-of-concept for the V2G technology. A simulation was carried out by The Energy Resources Institute (TERI) in Delhi to determine the utility of the V2G model in peak shaving, demand response, and demand-side management. The lessons learnt from the simulation suggest that the V2G model can be a viable option when combined with a financial incentive provided to the owners for feeding back units into the grid. With the increase in EV penetration across consumer segments, the V2G technology could help shave off peak load within small residential communities in the future, thereby reducing the load on the grid.

Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage

Carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) or carbon sequestration have been around for a long time. However, it has found another lease of life with technological evolution and the introduction of direct air capture technology. CCUS, an auxiliary technology to the two primary streams of mitigation and

adaptation to decarbonize the environment, also improves energy reliability. At present, the technology is in a nascent stage with only 26 CCUS facilities capturing around 36-40 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum globally. In India, there are only four facilities wherein carbon dioxide is recovered from the combustion of industrial flue gases and used to manufacture by-products.

India has a potential for carbon storage ranging from 5-400 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, mainly in geological formations. However, limited research and development on technical and economic feasibility, high capital and operational costs, and lack of regulatory/policy framework hinder market development of CCUS technologies in India. To address the R&D challenge, the Department of Science and Technology has established a national program on carbon dioxide storage to support research, development, and demonstration projects in 2020. It is also providing grant-in-aid support of up to $0.29 million under its Accelerating CCS Technologies (ACT) initiative. In the near future, industries are expected to lead the deployment of CCUS technologies with the increased focus on de-carbonization and net-zero pathways.

India has set a target of reducing the emission intensity of the economy by 33-35 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels under the Paris Agreement. Transitioning towards a clean and green economy requires an ecosystem-based approach with an emphasis on creating an enabling policy and regulatory framework, developing innovative financial instruments, and enhancing market demand and supply. The government has implemented various fiscal and financial assistance policies for generating power via renewable energy sources, improving industrial energy efficiency, and introducing electric vehicles for both private and public transport. However, there is limited focus on the development of new and innovative technologies through private sector engagement. Furthermore, between 2019 and 2020, the share of early-stage financing deals in the clean-tech sector fell sharply as compared to other sectors. To steer growth in clean-tech innovation, the government launched a global initiative, the ‘Mission Innovation CleanTech Exchange’ in 2021. This aims to drive global investment in research and development, demonstration, and commercialization of innovations in the clean-tech sector by catalyzing public-private capital. That said, there is a need to implement innovative financing approaches such as blended finance or rebates and incentive mechanisms as well as to provide scale-up financing for the commercialization of novel clean energy technologies.

Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative – Article by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Mumbai, 11 August – The article in BusinessWorld Disrupt titled, “Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative” authored by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap, was the 2nd one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with Business World Group.

The article talks how mid-market private equity deals that serve the traditional SME market is imperative when it comes to insulating the economy.

It’s a big YES but its’ not going to be easy. As we brace ourselves against the 3rd wave of COVID-19, the Indian economy continues to face distress. As per ILO, more than 400 mn in India are at risk of sinking deeper into poverty. While the government has been taking various fiscal measures to support recovery and resilience, private capital to has a significant part to play.

We saw a large number of tech start-ups mushroom in the COVID-19 world and VCs also had their hand full. The gig economy and e-commerce sectors show promise for generating employment, but they have to continuously keep raising capital to support the negative cash flows. It has been an uphill task for many to keep afloat. India ranks 3rd amongst global unicorns after USA and China with a combined valuation of USD 116 bn across 35 companies. With over $35.7 Bn in total funding, Indian unicorns are also the largest job creators and employers in the Indian startup ecosystem. Approximately, 70% of these unicorns are loss-making. Given the current global crisis, a financial collapse would be catastrophic for the surmounting unemployment rate in India. This is where our traditional sectors bring in longevity and resilience to the economy.

Unfortunately, in these difficult times, mid-market private equity deals saw a drop of approximately 32% compared to the pre-COVID-19 year. We also saw a drop of ~ 50% in traditional sectors that support employment and capital flow. This can be substantiated by 2 key data points – Firstly, a large part of the capital moved away from traditional businesses towards tech opportunities and COVID-friendly healthcare to insinuate at the “new normal”. Secondly, control/buyout deals saw increased traction compared to mid-market deals. Private Equity funds focused on mid-market opportunities saw their risk appetite going down with many uncertainties brought about with this pandemic. On the other hand, sovereign funds with significantly longer investment horizons have also seen dwindling risk appetite as they have been opting to do co-investments as opposed to direct investments.

We are seeing some interesting trends which could explain some of the gaps that need to be filled:

• Our country has a depleting count of risk-taking private equity funds including the sovereigns on one side and a piling dry powder on the other. As per a report published by Indian PE and VC association and Bain & Company, there was $8 bn in dry powder available with funds in 2020.

• Buyouts have recorded significant growth of almost 10x in the last decade

• Share of growth deals ($10-50 mn) or the missing middle (between the VCs and the large PE / buyout funds) has been going down in last decade

• Significant increase in the proportion of >$100 mn deals as a percentage of all deals in value compared to $10-50 mn deals. This also shows that PE funds are increasingly preferring larger ticket deals in mature companies leaving a growing vacuum in the SMEs for mid-market deals.

So what will help insulate our economy and businesses from these black swan events:

• More mid-market private equity funds that can support the traditional SMEs

• Mainstreaming of impact is now becoming a reality and we need more of that to happen soon. Limited partners now have a wide range of options to deploy their capital and General partners are using impact to differentiate and create value. TPG, Bain Capital, KKR, Partners Group, and others have created dedicated impact vehicles

• We need our very own DFI – not one but a few which focuses on specific themes and support businesses across their life cycle

• Need for higher domestic capital participation from pension/retirement funds in private equity funds. As Non-government funds, pension funds and gratuity funds can now invest up to 5% of their investible surplus in Category I and Category II AIFs registered with SEBI, this not only provides for financial stability in the Indian startup ecosystem but also boosts the confidence of the Indian market

• Lastly and more importantly, we need many more risk takers that can continue to show confidence and invest in the businesses even in difficult times

Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive advisor: Mitsui invests in PRESPL- India’s Leading Biomass Supply-Chain Management Company.

Mumbai, 05 Aug – Mitsui & Co., Ltd. (“Mitsui”, Head Office: Tokyo, President and CEO: Kenichi Hori) announced today that it will invest INR300 million (approximately USD4.1 million) in Punjab Renewable Energy Systems Pvt. Ltd. (PRESPL), one of the leading biomass supply-chain management companies in India.

PRESPL is involved in the collection, storage and processing of agricultural residues and the production of biomass briquettes and pellets to meet the growing demand for biomass fuel from India’s rapidly expanding bio-energy industry. PRESPL also provides a range of operation & maintenance, and other technical services, to the industry.

One of the major causes of air pollution in India today is the practice of burning straw stubble and other agricultural residues left after crops have been harvested. To help address this problem, the Government of India has introduced policies to promote the effective utilization of agricultural residues as a primary and supplementary fuel stock for the bio-energy industry. These policies are expected to contribute to the continued expansion of the bio-energy industry in India, as part of a flourishing circular economy.

Masaharu Okubo, Country Chairperson of Mitsui & Co. India Pvt. Ltd. said:

“We look forward to working together with PRESPL to grow its business by combining our respective areas of expertise and leveraging synergies with Mitsui’s diverse business portfolio.

The growth of PRESPL will contribute significantly to reducing air pollution and carbon emissions in India by effectively using agricultural residues as a fuel-stock for the bio-energy industry and providing a more sustainable alternative to fossil fuels. We, at Mitsui are grateful to be able to join PRESPL and contribute to the betterment of Indian society and other related stakeholders.

This investment is aligned with one of Mitsui’s important goals to create a more sustainable society, while furthering the expansion of our bio-energy business in India and around the world.”

Lt. Col. Monish Ahuja (Retd), Chairman & Managing Director, PRESPL said:

“On behalf of Team PRESPL and existing shareholders, I am delighted to welcome Mitsui as an investor and strategic partner. This investment from Mitsui will help PRESPL expand our footprint and accelerate the growth of the business as a market leader in India and overseas. In partnership with Mitsui, we aim to make a meaningful contribution to tackling climate change through the better utilization of biomass agri-waste for bioenergy.”

Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive and sole advisor to the PRESPL transaction across Series A, B and now Series C.

Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Investment Banking, Intellecap said:

“We are seeing a clear shift towards cleaner fuel across industries with Agri residue becoming a substitute and creating significant demand of ~600 million MT by 2031. PRESPL’s pioneer business model directly contributes to increasing farmer incomes by providing an additional source of revenue through sale of the feedstock which otherwise is destroyed. We are proud to be associated with PRESPL as an exclusive advisor since their Series A”

Off-Grid Solar Refrigeration: Cure to the Growing Vaccine Wastage Crisis – Article by Ankit Gupta and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in VC World

Mumbai, 20 July – The article in VC World, part of Business World titled, ‘Off-Grid Solar refrigeration: Cure to the growing vaccine crisis’ coauthored by Ankit Gupta, AVP, Intellecap and Kavya Hari, Senior Associate, Intellecap, was the 1st one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with BW Disrupt and VC World, part of the reputed Business World Group.

The article talks about the imperative need for off grid solar refrigeration , the cost effectiveness and key challenges and recommendations regarding off-grid solar refrigeration.

Need and importance of off-grid solar refrigeration for storage of vaccines

In India, reliability of grid electricity remains a significant challenge despite an electrification rate of 99.93% as per the Saubhagya Dashboard. According to the 2019-20 Rural Health Statistics, 28.4% of the sub-centres and 4.3% of the primary health centres (PHCs) in rural areas lack electricity supply; severely affecting the efficacy of health service delivery. A reliable source of electricity is required to enable refrigeration of medical supplies (like vaccines, blood, biological samples etc.) and ensure appropriate functioning of medical equipment.

In India, about 20-25% of all temperature sensitive health products (including vaccines) are spoilt or wasted due to insufficient refrigeration facilities. In terms of Covid-19 vaccination, the national average wastage is 6.3%, while the rate varies across states from 15% to less than 1%. Vaccine wastage occurs at both service and delivery levels – during storage, transportation and at vaccination centres. Majority of the vaccines (including Covishield and Covaxin) require a controlled temperature range from 2oC to 8oC to protect their potency. A vaccine’s efficacy is dependent on its potency, which can be reduced due to lack of proper storage and transportation facilities at the requisite temperature. Vaccine efficacy can be maintained by provision of reliable source of electricity through off-grid solar refrigerators.

Cost-effectiveness of off-grid solar refrigeration technologies

Solar direct drive (SDD) with phase change material (PCM) thermal battery and solar with battery (SWB) systems for ice lined refrigerators (ILRs) are the two most common types of technologies deployed in India. Technologies like SDD require only eight hours of sunlight to store thermal energy for a minimum of 78 hours of autonomy at an ambient temperature and a holdover time of 91 hours. SDD is also a more cost-effective technology mainly due to lower operational and maintenance costs at $8/litre compared to $16/litre for a SWB system. The higher cost for a SWB system is attributed to regular replacement of solar batteries.

In the absence of grid electricity supply, majority of the rural health centres use diesel generators that have higher operating costs (~$37/litre) due to recurring expenditure on fuel. Diesel generators also contribute to air pollution and have a detrimental impact on health and the environment. Typically, replacement of a diesel generation with solar technology for a 100-litre vaccine refrigerator (~1.9 kWh per day) can eliminate up to 720 kg of carbon dioxide emissions annually. Off-grid solar refrigerators thereby directly contribute to SDG 7 (clean energy) and SDG 13 (climate action).

Value chain of vaccine storage in India

The value chain for vaccine cold chain consists of a series of links that are designed to keep vaccines within WHO recommended temperature ranges, from the point of manufacture to the point of

administration. In India, vaccine distribution network is managed by four government medical store depots (GMSDs) located in Karnal, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. GMSDs procure vaccines from the manufacturers and supply it to ~53 state vaccine stores. These stores then distribute the vaccines at 114 regional, 736 district and 26,268 sub-district level cold chain points via insulated vans. There are limited vaccine transportation and refrigeration facilities at each of these stages which inhibit immunization services. According to the government, the country requires augmentation of cold storage from ~5.2 million in 2020 to 11 million in the next 5 years. The demand is highest for ice packs (44 lakhs in next 3 years) and vaccine carriers (5 lakhs in next 3 years), followed by demand for ILRs, cold boxes, among others. Innovative solar powered refrigeration technologies can reduce the existing supply chain gaps across cold chain points. A recent report by GOGLA and Intellecap mapped the total addressable market for off-grid solar vaccine storage at $811 million for last-mile delivery of services (i.e. health centres, chemists and ambulances) across rural India.

Ecosystem support for uptake of solar technologies

Given the ongoing pandemic, there has been a recent push from the government and development agencies for upscaling and deploying efficient solar technologies for vaccine storage as well as Covid-19 sample collection. In December 2020, the government announced usage of 29,000 cold chain points, 45,000 ILRs, and 300 solar refrigerators, among other applications for Covid-19 vaccine storage. By 2017, UNDP’s Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN) program had supported installation of 20 solar refrigerators and 45 solar equipment systems across nine states. There is application of new solar technologies such as solar-powered swab collection kiosks by SELCO India at various PHCs in Karnataka. The government is also driving the agenda of proper storage and utilization of vaccines through its policies like the “National Vaccine Policy” and “National Health Mission” and its agreement under the global “COVAX Facility”.

Key challenges and recommendations regarding off-grid solar refrigeration

The main challenges hindering the growth of the off-grid solar refrigeration market for vaccines are the long and cumbersome process of government tendering and limited awareness among stakeholders at the ecosystem level. The government agencies at the national/state level procure vaccine storage units through a tender process based on the least cost bidder criteria. Some of the early-stage entrepreneurs with innovative solar technologies are unable to compete at low prices or provide scale for participating in these tenders. Additionally, delays in approval and difficulty in payment clearance from the government discourages entrepreneurs and impacts their financial viability. Lack of awareness among policy makers and financiers on types and application of off-grid solar technologies and limited information on commercial viability further impedes uptake of these technologies.

The key recommendations for promotion of off-grid solar refrigeration pertain to three overarching themes of (i) generating awareness among stakeholders and end-users; (ii) enhancing the policy regime for solar cold chain in health care sector; and (iii) improving financial assistance for high cost (upfront) solar refrigeration facilities. Few specific recommendations include:

It is evident that the need of the hour is to improve health service delivery specially to reduce vaccine wastage through sustainable and cost-effective innovations. Thus, implementation of traditional initiatives (policy, awareness) along with innovative solutions (blockchain) can improve the overall effectiveness of off-grid solar refrigeration that can revolutionize the vaccine sector in India.

Reports & Policies

Our Impact Map

Sign up for our newsletter

© Copyright 2018 Intellecap Advisory Services Pvt. Ltd. - All Rights Reserved