-

BWDISRUPT

| August, 18, 2021Breaking Innovations in the Clean Technology Sector in India – Article by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Read More -

BWDisrupt

| August, 10, 2021Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative – Article by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Read More -

ET Energyworld.com

| August, 04, 2021Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive advisor: Mitsui invests in PRESPL- India’s Leading Biomass Supply-Chain Management Company.

Read More -

VC World

| July, 17, 2021Off-Grid Solar Refrigeration: Cure to the Growing Vaccine Wastage Crisis – Article by Ankit Gupta and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in VC World

Read More -

resonanceglobal

| July, 09, 2021Watch the Video – Vikas Bali, CEO, Intellecap at the Catalyst 2030 webinar speaking on ‘Catalyzing Collaboration between Companies and Social Enterprises’

Read More -

Next Billion

| April, 14, 2021Reimagining Agriculture in Kenya: Five Steps for Building Resilience and Food Security After a Catastrophic Year

Read More -

IDR

| March, 30, 2021Farm laws 2020: Efficiency vs equity – Sudhanshu Dikshit and Vivekanandhan T of Intellecap writes for India Development Review (IDR)

Read More -

PIB

| March, 04, 2021Government of India, FICCI and UN-based Better Than Cash Alliance come together for responsible merchant digitization in the North East, Himalayan Regions and Aspirational Districts

Read More -

Reuters

| February, 17, 2021Intellecap and Transform Rural India Foundation launch “India Agriculture and Food Systems – Circularity Action Platform” (IAFS-CAP) to promote circularity in production, processing and distribution of agriculture products in India

Read More - Conduct knowledge sharing sessions to highlight benefit of solar refrigerators over diesel and other technologies especially based on lifecycle costing.

- Establish a digital platform with data on technology applications and potential market segments to enhance knowledge about off-grid solar refrigerators.

- Empanel solar companies providing off-grid solar refrigerators through a bi-annual selection process to enable quick deployment of technology.

- Provide disincentives to health care centres for usage of diesel generators in favour of solar technologies (like off-grid solar refrigerators and solar PV systems).

- Provide a dedicated budget for implementation of DRE systems at health care centres through the existing national/state level policies.

- Aggregate financial assistance at the national/state level through external funds from development agencies, CSR funds, private foundations etc.

- Deploy/use innovations like blockchain to provide real-time visibility of vaccine distribution from manufacturing to administration and eliminate supply chain gaps.

Breaking Innovations in the Clean Technology Sector in India – Article by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Mumbai, 23rd August – The article in BusinessWorld Disrupt titled, ‘Pathbreaking Innovation in the Clean Technology Sector in India’ authored by Ashay Abbhi and Kavya Hari, Intellecap, was the 3rd one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with the Business World Group.

According to the Central Electricity Authority, as of May 2021, the share of renewable energy in India’s total installed capacity (383.3 GW) stands at around 25% (95.6 GW). However, in power generation, it accounts for only about 12% at 14.13 billion units (BU) against a total generation of 118.09 Bus

The article sheds light on how we can transition towards a clean and green economy with an ecosystem-based approach.

India is at the cusp of its energy transition journey driven by the 3D concept – Decarbonization, Decentralisation, and Digitization. Even as large-scale renewable energy is rapidly making strides towards cleaning and greening the grid, fossil fuel-based polluting power generation continues to dominate India’s energy mix. According to the Central Electricity Authority, as of May 2021, the share of renewable energy in India’s total installed capacity (383.3 GW) stands at around 25% (95.6 GW). However, in power generation, it accounts for only about 12% at 14.13 billion units (BU) against a total generation of 118.09 BUs. Despite the growing share of renewable energy in the power basket of India, the challenge of providing clean energy to the on-grid and off-grid consumers still looms large. On the occasion of World Renewable Energy Day, Intellecap explores the mega-trends in the clean energy and climate change space in India highlighting key technologies within India’s 3D energy transition concept that promise a cleaner, more efficient, and resilient energy sector.

Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen has recently gained traction as one of the fuels of the future. The term green is applied to the hydrogen production process when it is produced using renewable energy. The adoption of green hydrogen has the potential to decarbonize sectors with significant carbon emissions. It can be applied in the chemical and fertilizer industry for the production of ammonia and methanol, the steel industry as a reducing agent, commercial and residential heat production, power generation, and fuel for transportation. Currently, the country utilizes around six million metric tonnes of hydrogen. This demand is expected to rise to 11 million metric tonnes by 2029-30. Production of hydrogen of this magnitude can lead to large amounts of carbon emissions which can be avoided by promoting and scaling up green hydrogen.

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) has recently published the draft ‘National Hydrogen Energy Mission’ aimed at creating a green hydrogen value-chain, reducing production costs and phasing away from grey hydrogen (hydrogen produced from fossil fuels). The estimated cost of producing green hydrogen ranges from $3.6-5.8 per kg which is almost three times the cost of grey hydrogen. The recent indication from the government towards setting green hydrogen consumption obligations for the petroleum refining and fertilizer industry has led to traction from private sector and government players likewise. Notable examples include: Reliance Industries launched the India H2 Alliance (IH2A) to build the hydrogen economy; NTPC signed a MoU with Siemens for green hydrogen production from its RE plants; the Indian Oil Corporation plans to establish a green hydrogen plant to replace fossil fuels at its refinery; and Adani Enterprises is collaborating with Maire Technimont to implement green hydrogen projects.

Peer-to-peer Energy Trading through Blockchain

In the era of prosumers (consumers who produce their own electricity) peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading presents a viable solution to allow access to solar power for consumers with inadequate rooftop space or capital to set up solar power projects. Per this technology, excess energy from the solar rooftop plant of

a consumer can be sold to its neighbors. P2P trading uses blockchain technology to ensure transparent and reliable transactions. The transactions are carried out through smart contracts that can divert a pre-determined portion of energy to a consumer at a definite time, thereby encouraging decentralization and reducing the role of distribution companies and retailers. At present, the technology is only in the pilot stage and may take a few years to achieve universal acceptance. Significant resistance is expected from DISCOMs who may not like to see their high paying customers switch to energy trading. Moreover, the development of this infrastructure within high-density areas with limited rooftop space may not be financially viable.

India has already begun experimenting with P2P energy trading. BSES Rajdhani, in collaboration with blockchain technology provider Power Ledger, Australia, has created a solar oasis in Delhi’s grid-connected residential hub of Dwarka. The pilot project comprises 300 kW of solar power plants which services a group of gated communities. During the trial, residents with rooftop solar infrastructure were able to trade a total of 25 MWh of energy with their neighbors as well as with higher tariff commercial customers, minimizing the amount of energy that was spilled back to the grid.

Vehicle-to-Grid

Electric Vehicles (EVs) can use their batteries as decentralized storage systems for excess power when not in use, which can be fed into the grid through the vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology. EVs charged through solar-powered charging stations when combined together can integrate a considerable amount of renewable energy into the grid to help balance the load during peak hours. EV owners can be compensated in the form of direct payment per unit fed into the grid or through preferential EV charging tariffs. This bi-directional flow of energy can be especially useful when utilizing the time-of-day concept – EVs can use solar power to charge during the day and feed it back to the grid during the night. However, unless EVs scale up to the point where large amounts of energy can be stored in the batteries, V2G technology will remain a distant dream. Moreover, given the payment track record of cash-strapped DISCOMs, feeding energy into the grid may lead to financial turbulence for both the DISCOMs and the EV owners.

So far, research projects are underway in India to establish a proof-of-concept for the V2G technology. A simulation was carried out by The Energy Resources Institute (TERI) in Delhi to determine the utility of the V2G model in peak shaving, demand response, and demand-side management. The lessons learnt from the simulation suggest that the V2G model can be a viable option when combined with a financial incentive provided to the owners for feeding back units into the grid. With the increase in EV penetration across consumer segments, the V2G technology could help shave off peak load within small residential communities in the future, thereby reducing the load on the grid.

Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage

Carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS) or carbon sequestration have been around for a long time. However, it has found another lease of life with technological evolution and the introduction of direct air capture technology. CCUS, an auxiliary technology to the two primary streams of mitigation and

adaptation to decarbonize the environment, also improves energy reliability. At present, the technology is in a nascent stage with only 26 CCUS facilities capturing around 36-40 million tonnes of carbon dioxide per annum globally. In India, there are only four facilities wherein carbon dioxide is recovered from the combustion of industrial flue gases and used to manufacture by-products.

India has a potential for carbon storage ranging from 5-400 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, mainly in geological formations. However, limited research and development on technical and economic feasibility, high capital and operational costs, and lack of regulatory/policy framework hinder market development of CCUS technologies in India. To address the R&D challenge, the Department of Science and Technology has established a national program on carbon dioxide storage to support research, development, and demonstration projects in 2020. It is also providing grant-in-aid support of up to $0.29 million under its Accelerating CCS Technologies (ACT) initiative. In the near future, industries are expected to lead the deployment of CCUS technologies with the increased focus on de-carbonization and net-zero pathways.

India has set a target of reducing the emission intensity of the economy by 33-35 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels under the Paris Agreement. Transitioning towards a clean and green economy requires an ecosystem-based approach with an emphasis on creating an enabling policy and regulatory framework, developing innovative financial instruments, and enhancing market demand and supply. The government has implemented various fiscal and financial assistance policies for generating power via renewable energy sources, improving industrial energy efficiency, and introducing electric vehicles for both private and public transport. However, there is limited focus on the development of new and innovative technologies through private sector engagement. Furthermore, between 2019 and 2020, the share of early-stage financing deals in the clean-tech sector fell sharply as compared to other sectors. To steer growth in clean-tech innovation, the government launched a global initiative, the ‘Mission Innovation CleanTech Exchange’ in 2021. This aims to drive global investment in research and development, demonstration, and commercialization of innovations in the clean-tech sector by catalyzing public-private capital. That said, there is a need to implement innovative financing approaches such as blended finance or rebates and incentive mechanisms as well as to provide scale-up financing for the commercialization of novel clean energy technologies.

Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative – Article by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap in BusinessWorld Disrupt

Mumbai, 11 August – The article in BusinessWorld Disrupt titled, “Like in cricket, playing the middle overs is imperative” authored by Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Intellecap, was the 2nd one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with Business World Group.

The article talks how mid-market private equity deals that serve the traditional SME market is imperative when it comes to insulating the economy.

It’s a big YES but its’ not going to be easy. As we brace ourselves against the 3rd wave of COVID-19, the Indian economy continues to face distress. As per ILO, more than 400 mn in India are at risk of sinking deeper into poverty. While the government has been taking various fiscal measures to support recovery and resilience, private capital to has a significant part to play.

We saw a large number of tech start-ups mushroom in the COVID-19 world and VCs also had their hand full. The gig economy and e-commerce sectors show promise for generating employment, but they have to continuously keep raising capital to support the negative cash flows. It has been an uphill task for many to keep afloat. India ranks 3rd amongst global unicorns after USA and China with a combined valuation of USD 116 bn across 35 companies. With over $35.7 Bn in total funding, Indian unicorns are also the largest job creators and employers in the Indian startup ecosystem. Approximately, 70% of these unicorns are loss-making. Given the current global crisis, a financial collapse would be catastrophic for the surmounting unemployment rate in India. This is where our traditional sectors bring in longevity and resilience to the economy.

Unfortunately, in these difficult times, mid-market private equity deals saw a drop of approximately 32% compared to the pre-COVID-19 year. We also saw a drop of ~ 50% in traditional sectors that support employment and capital flow. This can be substantiated by 2 key data points – Firstly, a large part of the capital moved away from traditional businesses towards tech opportunities and COVID-friendly healthcare to insinuate at the “new normal”. Secondly, control/buyout deals saw increased traction compared to mid-market deals. Private Equity funds focused on mid-market opportunities saw their risk appetite going down with many uncertainties brought about with this pandemic. On the other hand, sovereign funds with significantly longer investment horizons have also seen dwindling risk appetite as they have been opting to do co-investments as opposed to direct investments.

We are seeing some interesting trends which could explain some of the gaps that need to be filled:

• Our country has a depleting count of risk-taking private equity funds including the sovereigns on one side and a piling dry powder on the other. As per a report published by Indian PE and VC association and Bain & Company, there was $8 bn in dry powder available with funds in 2020.

• Buyouts have recorded significant growth of almost 10x in the last decade

• Share of growth deals ($10-50 mn) or the missing middle (between the VCs and the large PE / buyout funds) has been going down in last decade

• Significant increase in the proportion of >$100 mn deals as a percentage of all deals in value compared to $10-50 mn deals. This also shows that PE funds are increasingly preferring larger ticket deals in mature companies leaving a growing vacuum in the SMEs for mid-market deals.

So what will help insulate our economy and businesses from these black swan events:

• More mid-market private equity funds that can support the traditional SMEs

• Mainstreaming of impact is now becoming a reality and we need more of that to happen soon. Limited partners now have a wide range of options to deploy their capital and General partners are using impact to differentiate and create value. TPG, Bain Capital, KKR, Partners Group, and others have created dedicated impact vehicles

• We need our very own DFI – not one but a few which focuses on specific themes and support businesses across their life cycle

• Need for higher domestic capital participation from pension/retirement funds in private equity funds. As Non-government funds, pension funds and gratuity funds can now invest up to 5% of their investible surplus in Category I and Category II AIFs registered with SEBI, this not only provides for financial stability in the Indian startup ecosystem but also boosts the confidence of the Indian market

• Lastly and more importantly, we need many more risk takers that can continue to show confidence and invest in the businesses even in difficult times

Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive advisor: Mitsui invests in PRESPL- India’s Leading Biomass Supply-Chain Management Company.

Mumbai, 05 Aug – Mitsui & Co., Ltd. (“Mitsui”, Head Office: Tokyo, President and CEO: Kenichi Hori) announced today that it will invest INR300 million (approximately USD4.1 million) in Punjab Renewable Energy Systems Pvt. Ltd. (PRESPL), one of the leading biomass supply-chain management companies in India.

PRESPL is involved in the collection, storage and processing of agricultural residues and the production of biomass briquettes and pellets to meet the growing demand for biomass fuel from India’s rapidly expanding bio-energy industry. PRESPL also provides a range of operation & maintenance, and other technical services, to the industry.

One of the major causes of air pollution in India today is the practice of burning straw stubble and other agricultural residues left after crops have been harvested. To help address this problem, the Government of India has introduced policies to promote the effective utilization of agricultural residues as a primary and supplementary fuel stock for the bio-energy industry. These policies are expected to contribute to the continued expansion of the bio-energy industry in India, as part of a flourishing circular economy.

Masaharu Okubo, Country Chairperson of Mitsui & Co. India Pvt. Ltd. said:

“We look forward to working together with PRESPL to grow its business by combining our respective areas of expertise and leveraging synergies with Mitsui’s diverse business portfolio.

The growth of PRESPL will contribute significantly to reducing air pollution and carbon emissions in India by effectively using agricultural residues as a fuel-stock for the bio-energy industry and providing a more sustainable alternative to fossil fuels. We, at Mitsui are grateful to be able to join PRESPL and contribute to the betterment of Indian society and other related stakeholders.

This investment is aligned with one of Mitsui’s important goals to create a more sustainable society, while furthering the expansion of our bio-energy business in India and around the world.”

Lt. Col. Monish Ahuja (Retd), Chairman & Managing Director, PRESPL said:

“On behalf of Team PRESPL and existing shareholders, I am delighted to welcome Mitsui as an investor and strategic partner. This investment from Mitsui will help PRESPL expand our footprint and accelerate the growth of the business as a market leader in India and overseas. In partnership with Mitsui, we aim to make a meaningful contribution to tackling climate change through the better utilization of biomass agri-waste for bioenergy.”

Intellecap’s Investment Banking Group was the exclusive and sole advisor to the PRESPL transaction across Series A, B and now Series C.

Gagandeep Bakshi, Director, Investment Banking, Intellecap said:

“We are seeing a clear shift towards cleaner fuel across industries with Agri residue becoming a substitute and creating significant demand of ~600 million MT by 2031. PRESPL’s pioneer business model directly contributes to increasing farmer incomes by providing an additional source of revenue through sale of the feedstock which otherwise is destroyed. We are proud to be associated with PRESPL as an exclusive advisor since their Series A”

Off-Grid Solar Refrigeration: Cure to the Growing Vaccine Wastage Crisis – Article by Ankit Gupta and Kavya Hari, Intellecap in VC World

Mumbai, 20 July – The article in VC World, part of Business World titled, ‘Off-Grid Solar refrigeration: Cure to the growing vaccine crisis’ coauthored by Ankit Gupta, AVP, Intellecap and Kavya Hari, Senior Associate, Intellecap, was the 1st one as part of a 24 article thought leadership series we have forged with BW Disrupt and VC World, part of the reputed Business World Group.

The article talks about the imperative need for off grid solar refrigeration , the cost effectiveness and key challenges and recommendations regarding off-grid solar refrigeration.

Need and importance of off-grid solar refrigeration for storage of vaccines

In India, reliability of grid electricity remains a significant challenge despite an electrification rate of 99.93% as per the Saubhagya Dashboard. According to the 2019-20 Rural Health Statistics, 28.4% of the sub-centres and 4.3% of the primary health centres (PHCs) in rural areas lack electricity supply; severely affecting the efficacy of health service delivery. A reliable source of electricity is required to enable refrigeration of medical supplies (like vaccines, blood, biological samples etc.) and ensure appropriate functioning of medical equipment.

In India, about 20-25% of all temperature sensitive health products (including vaccines) are spoilt or wasted due to insufficient refrigeration facilities. In terms of Covid-19 vaccination, the national average wastage is 6.3%, while the rate varies across states from 15% to less than 1%. Vaccine wastage occurs at both service and delivery levels – during storage, transportation and at vaccination centres. Majority of the vaccines (including Covishield and Covaxin) require a controlled temperature range from 2oC to 8oC to protect their potency. A vaccine’s efficacy is dependent on its potency, which can be reduced due to lack of proper storage and transportation facilities at the requisite temperature. Vaccine efficacy can be maintained by provision of reliable source of electricity through off-grid solar refrigerators.

Cost-effectiveness of off-grid solar refrigeration technologies

Solar direct drive (SDD) with phase change material (PCM) thermal battery and solar with battery (SWB) systems for ice lined refrigerators (ILRs) are the two most common types of technologies deployed in India. Technologies like SDD require only eight hours of sunlight to store thermal energy for a minimum of 78 hours of autonomy at an ambient temperature and a holdover time of 91 hours. SDD is also a more cost-effective technology mainly due to lower operational and maintenance costs at $8/litre compared to $16/litre for a SWB system. The higher cost for a SWB system is attributed to regular replacement of solar batteries.

In the absence of grid electricity supply, majority of the rural health centres use diesel generators that have higher operating costs (~$37/litre) due to recurring expenditure on fuel. Diesel generators also contribute to air pollution and have a detrimental impact on health and the environment. Typically, replacement of a diesel generation with solar technology for a 100-litre vaccine refrigerator (~1.9 kWh per day) can eliminate up to 720 kg of carbon dioxide emissions annually. Off-grid solar refrigerators thereby directly contribute to SDG 7 (clean energy) and SDG 13 (climate action).

Value chain of vaccine storage in India

The value chain for vaccine cold chain consists of a series of links that are designed to keep vaccines within WHO recommended temperature ranges, from the point of manufacture to the point of

administration. In India, vaccine distribution network is managed by four government medical store depots (GMSDs) located in Karnal, Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata. GMSDs procure vaccines from the manufacturers and supply it to ~53 state vaccine stores. These stores then distribute the vaccines at 114 regional, 736 district and 26,268 sub-district level cold chain points via insulated vans. There are limited vaccine transportation and refrigeration facilities at each of these stages which inhibit immunization services. According to the government, the country requires augmentation of cold storage from ~5.2 million in 2020 to 11 million in the next 5 years. The demand is highest for ice packs (44 lakhs in next 3 years) and vaccine carriers (5 lakhs in next 3 years), followed by demand for ILRs, cold boxes, among others. Innovative solar powered refrigeration technologies can reduce the existing supply chain gaps across cold chain points. A recent report by GOGLA and Intellecap mapped the total addressable market for off-grid solar vaccine storage at $811 million for last-mile delivery of services (i.e. health centres, chemists and ambulances) across rural India.

Ecosystem support for uptake of solar technologies

Given the ongoing pandemic, there has been a recent push from the government and development agencies for upscaling and deploying efficient solar technologies for vaccine storage as well as Covid-19 sample collection. In December 2020, the government announced usage of 29,000 cold chain points, 45,000 ILRs, and 300 solar refrigerators, among other applications for Covid-19 vaccine storage. By 2017, UNDP’s Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN) program had supported installation of 20 solar refrigerators and 45 solar equipment systems across nine states. There is application of new solar technologies such as solar-powered swab collection kiosks by SELCO India at various PHCs in Karnataka. The government is also driving the agenda of proper storage and utilization of vaccines through its policies like the “National Vaccine Policy” and “National Health Mission” and its agreement under the global “COVAX Facility”.

Key challenges and recommendations regarding off-grid solar refrigeration

The main challenges hindering the growth of the off-grid solar refrigeration market for vaccines are the long and cumbersome process of government tendering and limited awareness among stakeholders at the ecosystem level. The government agencies at the national/state level procure vaccine storage units through a tender process based on the least cost bidder criteria. Some of the early-stage entrepreneurs with innovative solar technologies are unable to compete at low prices or provide scale for participating in these tenders. Additionally, delays in approval and difficulty in payment clearance from the government discourages entrepreneurs and impacts their financial viability. Lack of awareness among policy makers and financiers on types and application of off-grid solar technologies and limited information on commercial viability further impedes uptake of these technologies.

The key recommendations for promotion of off-grid solar refrigeration pertain to three overarching themes of (i) generating awareness among stakeholders and end-users; (ii) enhancing the policy regime for solar cold chain in health care sector; and (iii) improving financial assistance for high cost (upfront) solar refrigeration facilities. Few specific recommendations include:

It is evident that the need of the hour is to improve health service delivery specially to reduce vaccine wastage through sustainable and cost-effective innovations. Thus, implementation of traditional initiatives (policy, awareness) along with innovative solutions (blockchain) can improve the overall effectiveness of off-grid solar refrigeration that can revolutionize the vaccine sector in India.

Watch the Video – Vikas Bali, CEO, Intellecap at the Catalyst 2030 webinar speaking on ‘Catalyzing Collaboration between Companies and Social Enterprises’

Watch the Video – Vikas Bali, CEO, Intellecap at the Catalyst 2030 webinar speaking on ‘Catalyzing Collaboration between Companies and Social Enterprises’

Mumbai, 09 July – Vikas Bali, CEO, Intellecap was a Speaker at the Resonance & Catalyst 2030, on the topic ‘Catalyzing Collaboration between Companies and Social Enterprises’ talking about how & why companies partner with social enterprises to scale impact in their value chains and beyond.

Moderated by Steve Schmida, Founder and Chief Innovation Officer of Resonance, the panel comprised of Alexandra van der Ploeg. Head of Corporate Social Responsibility at SAP and Naa Akwetey, Senior Vice President, Strategy and Business Development, at mPharma.

To watch the webinar video – Click Here

More on the Session ‘What happens when large companies join forces with Innovative Social Enterprises’:

Over a relatively short period, sustainability has become central to the corporate world. In 2011, 20% of S&P 500 companies published sustainability reports. By 2019, 90% did. And this shift is global: A 2020 survey of 5,200 companies across 52 countries found that 80% now report on sustainability, with a significant majority linking their business activities to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The question is: what next? How should companies turn pledges and promises and reports into lasting and effective action?

The short answer is that collaboration is key—and leading companies know that they need to bring new partners to the table. Catalyst 2030 and Resonance just released new research on how large corporates are teaming up with innovative social enterprises in creative and powerful ways to advance social and environmental impact.

To build on this work, Resonance’s Steve Schmida, spoke with three cross-sector leaders who are pioneering corporate-social enterprise partnerships:

Alexandra van der Ploeg, Head of Corporate Social Responsibility at the global technology company SAP, where she is responsible for setting the global direction of CSR through strategic partnerships and programs.

Naa Akwetey, Senior Vice President, Strategy and Business Development, at mPharma, an award-winning healthcare social enterprise headquartered in Ghana and operational in Nigeria, Kenya, Zambia, Rwanda, and Malawi. mPharma partners across pharmaceutical supply chains to expand access to affordable healthcare in Africa.

Vikas Bali, CEO of the global impact advisory Intellecap, which works to build enabling ecosystems and channel capital to create a more sustainable and equitable society. At Intellecap, Bali is focused on developing innovative business models for emerging markets across Asia and Africa.

Below are three key takeaways on how companies and social enterprises can work together to solve pressing challenges and advance corporate sustainability.

3 Takeaways on How Companies and Social Enterprises Can Work Together:

Huge value can be unlocked by making social enterprise partnerships “core business”—but there are challenges to scale.

For more than a decade, SAP has been engaging with and supporting social enterprises. But a few years ago, “We became aware of this completely new opportunity to partner with social enterprises that we’d not had on our radar yet—and that’s social procurement,” SAP’s Alexandra van der Ploeg said. Social procurement allows companies to engage social enterprises—as suppliers and service providers—directly within their existing value chains. “We were quickly convinced about the business case for social procurement, and we realized that we had an opportunity to unlock significantly higher investments for social impact than what any corporate philanthropic vehicles could do.”

The World Bank estimates that 2019 global procurement spend was at least $14 trillion. As van der Ploeg noted, directing only a small fraction of this money—which gets spent regardless—toward social enterprises and diverse suppliers would accelerate impact in ways unimaginable through traditional CSR. SAP alone has determined that, through procurement, it could channel $60 million per year to social enterprises and diverse suppliers by 2025. Across Fortune 500 companies, this number is around $25 billion.

“This is not about being philanthropic,” added van der Ploeg. “It really engages the whole of SAP’s business—including procurement, sales, product development, and CSR. It’s about doing more with the money that we are spending anyway through procurement—and making that money go further by delivering social impact as well.”

The potential is big; yet there are challenges for scale. Much needs to be done to help social enterprises build their capacity to be “corporate ready”—and for corporates to adapt systems, procurement policies, and internal incentives to better integrate social enterprises. Another challenge for companies? How to identify, verify, and connect with viable social enterprise partners. SAP is using existing tools to help create solutions: For example, the SAP Ariba Network is the largest B2B marketplace in the world, supporting nearly $3.5 trillion in transactions each year. In partnership with leading social enterprise organizations, SAP is working to use Ariba to connect corporate-ready social enterprises to other companies eager to engage in social procurement.

When done right, partnering with social enterprises offers corporations tremendous strategic value.

The value that corporations offer to social enterprises may be obvious: Access to capital, markets, consumers, research, infrastructure, and so on. “There are millions of reasons for them to partner,” said Intellecap CEO Vikas Bali. But he also offered three key reasons why corporations should invest in partnerships with social enterprises.

First, social enterprises often bring intimate, boots-on-the-ground access to the first and last mile—to the billions of people who will increasingly act as producers and consumers across global value chains. Second, social enterprises provide a pathway to innovation and invention that large, bureaucratized companies struggle to replicate. Social enterprises can pivot their models quickly; they can experiment; and this gives corporates a low-cost method to understand and solve for new consumers and markets.

“Third, and this is a little controversial, instead of access to stock market value, companies are understanding that they need access to societal value creation,” Bali said. Companies are recognizing that the market value of their business must now be measured in parallel with how valuable it is to society. “I do clearly see a trend where large corporates are saying we need to do the right thing, we need to be seen to be doing the right thing. This is not just giving away small amounts of money through CSR, it’s about being a responsible, sustainable, resource-efficient business ourselves, and thereby there is this need to partner with social or impact enterprises.”

mPharma’s Naa Akwetey added that social enterprises, which are embedded in local communities, can provide corporates with essential “perspective,” on-the-ground understanding, and market data that otherwise get buried in global value chains. mPharma, for instance, can give feedback to multinational pharmaceutical companies about patient behavior, preferences, and buying choices in specific markets and across countries. All of these insights are of particular importance given that the markets where corporations tend to have limited optics and sparse data—those in emerging economies—are often the markets where the most growth is expected in coming decades.

Partnerships between corporations and social enterprises don’t exist in a vacuum. True success often calls for an ecosystem approach.

A great idea is not enough. To grow, an enterprise needs access to capital, to talent, to markets, and to legal and technical assistance. “All of these things have to be kept in mind as large corporates start dealing with impact enterprises,” says Bali. “It’s not just buying into a great idea; it’s buying into an idea and saying we will develop the ecosystem for this idea to sustain, to flourish, to become scalable.”

Van der Ploeg noted that SAP’s social procurement programs are, at the moment, focused more on investment in capacity building than social procurement proper. SAP is taking the time to build the foundation that will make social procurement viable—for SAP, for social enterprises, for other companies, and for the ecosystem at large. Two examples of ecosystem building efforts currently underway are SAP and MovingWorld’s S-GRID Accelerator and the work of the COVID Response Alliance for Social Entrepreneurs.

“This work is trying to address problems that society has not been able to solve for thousands of years, so there are no quick fixes, there are no easy solutions, and these solutions are not one-dimensional. It will require an ecosystem approach,” Bali said. “Ecosystem-building is a fine art, and lots of stakeholders need to come together to take the journey forward.”

Reimagining Agriculture in Kenya: Five Steps for Building Resilience and Food Security After a Catastrophic Year

Nairobi, April 14, 2021 : Michael Omega, Rachael Wangari and Daniel Kitwa, from Intellecap Africa coauthored the article ‘Reimagining Agriculture in Kenya: Five Steps for Building Resilience and Food Security After a Catastrophic Year’ as part of our strategic content tie up with Next Billion.

To say that we need to reimagine the agricultural and food systems in Kenya would be an understatement. Indeed, 2020 brought an unholy trinity of crises that threatened both lives and livelihoods, and which served as a wake-up call about the fragility of the country’s agricultural sector and overall food system. First, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted practically everything that was previously considered normal. This was followed by the largest desert locust upsurge in 70 years and flash floods that affected more than three-quarters of the country — including the food-producing counties in Kenya’s Western, Rift Valley and Central provinces.

The following numbers put these three threats into perspective:

-The announcement of the country’s first COVID-19 case in March 2020 and the resultant containment measures had far-reaching effects on the flow of goods and services across the food system, straining the livelihoods of millions of urban and rural dwellers while increasing food prices for consumers. As of last September, 6.2 million Kenyans were in a food-insecure situation, with an even higher number unable to access and/or afford safe and nutritious foods.

-Desert locusts are considered the most destructive pest in the world, with an average swarm (estimated between 40-80 million locusts covering one square km) eating the same amount of food in one day as about 35,000 people. Hence, the impact of the swarm covering 2,400 square kmsand containing billion of locusts that was reported in Kenya was more than catastrophic.

-The flash floods the country experienced were only comparable to the 2016 El Niño flooding that was responsible for severe food insecurity in the country. Between March and May 2020, the floods affected more than 233,000 people, with 116,000 people displaced and 194 deaths. Further, acres of farmland were destroyed and thousands of livestock killed, while key infrastructure such as roads, bridges and schools were left in ruins.

These grim statistics remind us that it is possible for a single catastrophic event to wipe out decades of progress for communities, while multiple catastrophes can easily overwhelm entire countries. And as the world gets increasingly connected, we’ve become more vulnerable than ever before to these types of compounding crises.

THE NEED FOR RESILIENCE IN KENYAN AGRICULTURE

Kenya’s recent struggles are also a reminder that climate change is already accelerating and intensifying natural disasters. The warming climate is closely intertwined with the performance of food systems, and crises that impact these systems often disproportionately affect the vulnerable. For that reason, resilience is a goal that should not only be discussed in boardroom meetings, brainstorming sessions and keynote addresses, but rather one that should be translated into the everyday business environment in cities and villages worldwide. Essentially, resilience should be a way of life, a lens through which policy is designed, strategy is implemented and commerce is facilitated. And the agricultural sector should be a key focus of these efforts.

Kenya, a perennial net importer of food, imported about KES 17.2 billion in December 2020 alone. For a country with an increasing population and a continued dependence on rain-fed agriculture, this spending is bound to go up if nothing is done about it. Kenya’s situation with respect to food security and its chronic dependence on imports is not unique in sub-Saharan Africa. However, its position as an economic hub in East Africa suggests that any efforts it makes toward building resilience in its food systems may offer transferable blueprints, models and pathways that can be implemented in other emerging markets and contexts. So it’s particularly valuable to explore solutions to Kenya’s current food security challenges.

The following points (in no particular order of importance) highlight some of the ways we can reimagine Kenya’s entire agricultural value chain and food system.

REIMAGINING FARM LABOR

Experts estimate the average age of the Kenyan farmer to be 61 years. In a country where 75% of the population is under 35 years, this essentially means that the sector does not attract the most productive labor assets — young workers. With older farmworkers, the risk of decreased productivity and overall output is ever-present. Further, this population is slow to adopt technology and innovation. We, therefore, need to explore policies, incentives and interventions that increase the youth’s participation in the agriculture labor force. This should be a holistic approach that includes enhancing access to technology, capital and knowledge for prospective young farmers so that the barriers for entry are not only reduced but ultimately eliminated over time.

REIMAGINING THE FOOD STORAGE INFRASTRUCTURE

For a country that loses up to 20-30% of its production post-harvest, increasing and innovating on both national- and farm-level storage should be a top priority for key stakeholders. At a national level, food reserve storage is a relatively cheap public insurance policy against the tremendous uncertainties caused by climate change for the country’s food system. However, the National Cereals and Produce Board — the national food reserve agent — has faced multiple financial and operational challenges that have led to calls for the privatization of the institution. At the farm level, the adoption of productive renewable energy in activities such as refrigeration (cold storage), drying (solar dryers) and especially milling can increase the nutritional and monetary value of farm produce, and lengthen its shelf life.

REIMAGINING AGRICULTURE POLICY

Public policy plays a key role in the agricultural sector’s prospects. Kenya’s leadership will need to explore new and ground-breaking policy frameworks that set a path toward resilience. For instance, some critical measures include: developing policies to enhance food processing; establishing “localized” (county-level) climate change action plans and climate risk policies; and expanding budgetary capacities to respond to climate-related events that impact farmers. These approaches should be developed at both the national level and at the county level where implementation happens. Continuous monitoring and progress checks should be embedded into the process flow, to ensure that momentum is not lost and transparency is maintained.

REIMAGINING AGRICULTURE FINANCING

The cost of capital remains high for farmers and aggregators, especially given the risk-averse nature of the pool of local institutional capital available. Some farmers may not have a credit history outside of their co-operatives and SACCO funding partners, thus limiting their ability to tap into the additional sources of capital that exist. Access to finance should involve creating localized startup hubs away from the big cities, so that funding networks are available to agricultural players outside the country’s metropolitan areas. (Sadly, most incubation hubs are located in Nairobi.) The challenge then becomes how to localize these networks. Working with agricultural departments and the small and medium enterprise-focused infrastructure provided by counties can be one way of directing this support to businesses at the local level. Public and private investors can also explore innovative financing solutions such as: gender lens investing targeting women farmers; crowdfunding platforms that invest in African-owned farming infrastructure; portfolio-based lending where smallholder farmers can be aggregated and their assets securitized into a sizeable financing round; and impact-linked interest rate lending models.

REIMAGINING FARMING ITSELF

Behavior change among farmers should definitely be a key focus area in Kenya’s quest to become more resilient. This involves everything from the most basic of strategies, like crop rotation, to the most complex — such as a completely mechanized end-to-end approach to agriculture. Farmers need to unlearn common but less-effective methods, so as to relearn new ones. Behavior change should also involve consumers, who need to embrace new dietary patterns above and beyond the traditional staple foods, so as to trigger the market demand that would motivate farmers’ decisions, which are ultimately driven by what the buyer wants. For instance, can public school feeding programs incorporate diet choices that incentivize new, positive farming behavior and build new agricultural value chains, such as including new types of fruit orders, or even exploring camel or goat milk instead of cattle?

CONCLUSION

While the above list is certainly not conclusive, it represents a new way of thinking and includes the critical building blocks that define what resilience really means from an agricultural point of view. Kenya’s Vision 2030 aspirations are closely aligned with the United Nations’ SDG ambitions, and food security is part of the current government’s “Big Four” agenda. But while these intentions are encouraging and praiseworthy, long-lasting progress in boosting food security and agricultural productivity and improving livelihoods for farmers and vulnerable communities will only be achieved through an action-based and resilience-focused approach. Kenya must learn from past failures, build on our successes and strive to reimagine our future. To that end, the traumatic events of 2020 were an important lesson for us: As George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Farm laws 2020: Efficiency vs equity – Sudhanshu Dikshit and Vivekanandhan T of Intellecap writes for India Development Review (IDR)

Mumbai, March 30 –Intellecap’s Sudhanshu Dikshit and Vivekandhan T co-authored an article, “Farm Laws 2020: Efficiency Vs Equity” for India Development Review (IDR).

In the article, talking about the new farm laws, the coauthors opine that while there is agreement on the importance of improving food production and productivity, there are differing views on the ways to achieve both.

The new farm laws have become a politically contentious issue nationally, but if one were to steer clear of the political rhetoric, it becomes apparent that at the heart of the issue is the long standing efficiency vs equity debate.

Those on the efficiency side highlight the long overdue agri-sector reforms to move the sector from its stagnancy to higher levels of production and productivity. People on this side also bat for reduction of the government’s direct participation and an increased role for market forces (including more private players in agriculture).

On the other hand, those arguing for equity look at agriculture as a livelihood option for large numbers of small and marginal farmers. As a result, they oppose a reduction of the state’s role and express reservations about whether the farmers’ interests will be protected in a free market scenario.

Understanding how small and marginal farmers work

As per the Agriculture Census of 2015-16, approximately 86 percent of the farm holdings in India fall under the small and marginal category (up to two hectares). This small and marginal land holding, in turn, contributes to about 47 percent of the total agriculture land under cultivation. Looking at these figures, it is abundantly clear that small and marginal farmers’ productivity plays a critical role in improving the overall productivity of the sector.

Successive partitioning of agriculture land over generations has reduced the average size of the operational farm holdings, from an average size of 2.28 hectares in 1971 to 1.08 hectares in 2016. This small land holding is the core challenge for increasing farm productivity: The cost of producing one quintal of wheat varies drastically across different farm holding sizes.

Approximately 86 percent of the farm holdings in India fall under the small and marginal category

So, while one might argue that the productivity of a small farm holding is likely to be high because of better control on farm practices, it is important to understand that in these smallholdings, contribution of self and household labour is not monetised as a cost. There is actually an opportunity cost to this household labour; however the absence of gainful employment opportunities in rural areas makes way for this disguised unemployment.

While large and medium farmers are in a better position to leverage technology and manoeuvre economies of scale to their benefit, small and marginal farmers are unable to do either.

Small holder farmers face challenges regarding economies of scale on farm inputs as well as outputs. In comparison with large and medium farmers, they spend more on per unit of farm inputs (seeds, fertilizer and pesticides) but experience lesser realisation on per unit of commodity sale. This disparity does not get compensated in a free market scenario wherein small holder farmers have to compete on equal footing with large and medium farmers.

Looking at the farm laws through the lens of small and marginal farmers

In this context, it becomes important to analyse the new farm laws 2020 and see how they may potentially play out for small holder farmers.

If free market forces are unleashed on an existing set of actors, the existing power dynamics will determine who gets how much

The larger intent of the farm laws is to increase private sector investment across the entire agriculture value chain. Among the laws, the contract farming act enables legal provisions for private sector to enter into contractual arrangements with farmers and improve primary production. These contract farming arrangements have the potential to leverage private investments to improve farm level infrastructure like irrigation facilities, poly houses, trellis, etc. Improving infrastructure, along with the price assurance provisions in contract farming can provide the right incentives for small holder farmers to move away from subsistence cereal crop farming to commercial cash crop farming. This market oriented incentive for small and marginal farmers has the potential to reduce, and in certain cases, replace the existing need for support from development intervention agencies like nonprofits and government departments.

However, the above economic argument does not factor in prevailing power dynamics among different economic actors in the current agriculture market. Practitioners with even little exposure to ground realities will appreciate that if free market forces are unleashed on an existing set of actors, the existing power dynamics among the actors will determine who gets how much. This is the fundamental premise of the equity school of thought, which has concerns regarding the protection of small holder farmers’ interests and hence they are opposed to the removal of government participation.

The average farmers’ share in the end consumer rupee for 16 major food items is in the range of INR 28 paise to INR 78 paise

In its publication Supply Chain Dynamics and Food Inflation in India (2019) the RBI has estimated the average farmers’ share in the end consumer rupee for 16 major food items is in the range of INR 28 paise to INR 78 paise. The report also highlighted that among factors critical for increase of farmers’ realisation, are the literacy levels and the availability of market information, as these two factors empower the farmers to negotiate better with their buyers and get a better price for their outputs. In the absence of market information and low literacy, small and marginal farmers are at a greater risk of being exploited by other market players (traders, processors etc).

Where do we go from here?

As a country, we do have examples of market liberalisation in many sectors, the most prominent one being the economic liberalisation of the 90s. Those reforms did increase production and productivity. The private sector had championed these initiatives and they were duly aided by increased supply of credit, access to technology, and favourable government policies. As a consequence, employment opportunities increased in these sectors and the overall economy boomed. It therefore appears that as long as there is growth in market demand, micro and small producers can coexist with large producers.

But there are larger questions that we must consider-

– Is it prudent to compare the predicament of relatively well organised sectors like manufacturing to that of agriculture, which is less organised and has higher levels of disaggregated production?

– Have we exhausted all other means and is this the only route left to improve total crop production and average crop productivity?

– Have we focused on small and marginal farmers as a separate constituency in our efforts to improve food production?

In the overall efficiency vs equity debate, there is no opposing view regarding the importance of improving production and productivity to meet the future food demand in the country. However, there are differing views on the ways to achieve it. By taking a free market approach, the new farm laws have been criticised as inequitable, as they fail to account for empowering small and marginal farmers.

Intellecap Acquires 100% Stake In NR Management Consultants

Intellecap, the advisory arm of Aavishkaar Group announced 100% acquisition of NR Management Consultants India Private Limited (NRMC) to drive capital towards Natural resource driven Carbon Sequestration solutions to mitigate Climate change.

Intellecap is a global consulting firm dedicated to finding solutions that mitigate global risks of inequity in areas such as Impact investing, Climate Change and Gender. NRMC has deep research focus and understanding of natural resources and rural development in India and South East Asia. Drawing on its focus on nurturing entrepreneurship, Intellecap, through this acquisition looks to strengthen its Global positioning in Climate Change by incubating new initiatives and channelize strategic pools of capital to achieve tangible outcomes.

Speaking about the acquisition, Vikas Bali, CEO, Intellecap said, “Our objective of acquiring NRMC is focused on strengthening our resolve to build an effective Natural Resource based climate resilience strategy and drawing capital and delivering inclusive interventions through them. We see Climate change as humanities biggest challenge and Intellecap and Aavishkaar Group are committed to being significant part of the solution to this global problem. I invite all likeminded institutions, DFIs, Donors and commercial investors with focus on Climate Change to join hands with us, as together we can deliver real change and impact”

Speaking about the acquisition, Vineet Rai, Founder and Chairman, Aavishkaar Group said, “I am thrilled by this acquisition by Intellecap. Aavishkaar Group identifies Climate Resilience Investing as a Global Mega trend for the next decade and Intellecap has a big responsibility to lead the group in showing us solutions that would help us allocate capital effectively to combat Climate risk and offer true Resilience.”

“Intellecap and through it, the Aavishkaar Group offers a wide umbrella to NRMC expertise in Natural Resources. We all acknowledge that Climate change is the biggest challenge humanity is facing and with this partnership we would be able to use our knowledge and deep understanding of associated development challenges to drive capital toward real solutions that address climate resilience,” said Jayesh Bhatia, Founding Director, NRMC.

Government of India, FICCI and UN-based Better Than Cash Alliance come together for responsible merchant digitization in the North East, Himalayan Regions and Aspirational Districts

Mumbai, March 04 : The Government of India, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), and UN-based Better Than Cash Alliance today hosted Merchant Digitization Summit 2021: Towards Aatma Nirbhar (Self Reliance) Bharat with special focus on Himalayan Regions, North East Regions and Aspirational Districts of India.

The Summit brought together leaders from the public and private sectors for the Responsible Merchant Digitization Summit to accelerate responsible digitization of merchants in India’s North-Eastern and Himalayan regions, and Aspirational districts. Empowering women merchants who play critical roles in their communities is one of the priorities to help achieve the mission of Digital India. This Summit is part of the series of Learning Exchange amongst all States and Union Territories under which DEA had also co-organized the webinar titled “Unlocking the value of Fintech in promoting Digital Payments’ on December 9, 2020.

Intellecap was a proud Technical Partner to the UN based “Better Than Cash Alliance” (BTCA) at the Merchant Digitization Summit 2021, which saw participation and commitments to action for merchant digitization from the central and state governments, industry, and civil society organizations. The stakeholders discussed the challenges, solutions and potential for collaboration to scale up the merchant digitization efforts in the North-East, Himalayan Region, and Aspirational Districts across India, with a special focus on digitising payments for women merchants.

“The Government, under the leadership of the Honorable Prime Minister, is taking bold steps towards an inclusive Digital India,” said ShriK. Rajaraman, Additional Secretary, Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance. “Along with the increased focus on ‘Make in India’ through AatmaNirbhar Bharat Scheme, responsible digitization must more strongly include rural networks such as Self Help Groups and community enablers to create the local digital ecosystems to help millions of merchants join the formal economy, access credit, and grow their business.”

From an average of 2-3 billion digital transactions monthly[1], India has set ambitious target for 1 billion digital transactions per day[2]. Person to merchant (P2M) digital payment transactions will scale to 10-12 billion transactions every month to contribute to India’s digital economy. This is an enormous opportunity for digitized merchants. However, most digital payments solutions designed for smart phone whose penetration amongst merchants in these focus regions is very low. There was consensus during today’s Merchant Digitization event that an industry-level approach was required to address the unique and fundamental challenges including gender targeting in national, regional and state-level merchant initiatives.

Smt. Reema ben Nanavaty, Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), a Padma Shri recipient, applauded this focus on women merchants in the priority regions from the Government and the private sector, saying “our experience at SEWA shows that technology when put in to the hands of women they put it to their best use for economic security, asset creation, food security, and bringing support services such as health care, and nutrition at the doorstep of citizens”.

“Merchants, including kirana shops, emerged as local saviors during COVID-19, proving themselves to be both agile and resilient. It also increased the pace of digitization among kiranas.” said Shri Dilip Chenoy, Secretary General, FICCI. “As industry leaders, we are thrilled to support the Government in its focus on women merchants as an economic priority and build greater trust in the Himalayan Region, the North East, and in the aspirational districts with our members.”

The participants agreed that the National Language Translation Mission can be used to disseminate digital payments information, privacy clauses and consent in local languages for trust and empowerment. They also identified opportunities to address the challenges of connectivity, access to smart phones, and digital literacy for merchants at the last mile.

“Taking active measures to ensure merchants are protected from risks such as loss of privacy, exposure to fraud, and unauthorized fees are the tenets of the responsible digital payments guidelines,” said Keyzom Ngodup Massally, Head of Asia-Pacific, Better Than Cash Alliance. “Our member Hindustan Unilever with FICCI and other FMCG leaders have joined the Government to ensure that fairness is systematically embedded in merchant digitization.”

The Summit, organized with technical assistance of Intellecap, saw representatives from Telangana, J&K, Maharashtra, Bihar, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Manipur, Nagaland, Mizoram, Sikkim, Uttar Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Meghalaya, Dadar and Nagar Haveli, Delhi, and Daman and Diu, among othersdiscuss solutions that can be scaled across all aspirational districts and the focus regions.

The Government, FICCI, and the Better Than Cash Alliance will continue their partnership this year with catalytic actions to achieve the industry level commitment of responsible digitization of merchants agreed during today’s event.

Intellecap and Transform Rural India Foundation launch “India Agriculture and Food Systems – Circularity Action Platform” (IAFS-CAP) to promote circularity in production, processing and distribution of agriculture products in India

Intellecap and Transform Rural India Foundation launch “India Agriculture and Food Systems – Circularity Action Platform” (IAFS-CAP) to promote circularity in production, processing and distribution of agriculture products in India

Mumbai 12th February – In their quest to solve problems for the smallholder farmers, businesses and consumers, Intellecap and Transform Rural India Foundation today announced the launch of IAFS-CAP to promote circularity in production, processing and distribution of agriculture products (food, fibre and fuels). As part of this initiative, they are looking to operationalize 6-7 projects across the country impacting 1,00,000 farmers, several businesses and consumers while scaling at least 3 innovations in technology and business models within three years in the circularity space in agriculture and food sectors.

The system of circularity in agriculture is based on four basic principles – arable land should be used primarily to produce plant biomass for human consumption; by-products from food production, processing and consumption should be recycled back in the food system; adoption of the principles of regenerative agriculture and finally promoting consumption at low trophic levels.

The platform will operationalize challenge funds for surfacing circular technologies and business models, help them achieve proof of concept, curate pilots and scale them to help further the circularity agenda in agriculture and food sector in India. Further, the platform will enable farmer collectives and contract farming enterprises to access technology, philanthropic capital and premium markets. It will also enable sector stakeholders to curate partnerships to ensure that adequate quantities of agricultural produce, bearing the right quality specifications, are made available to processors, exporters, organized retail and e-commerce platforms in a timely manner. Additionally, the platform will also be capable of undertaking deep research and advocacy to identify best practices, ecosystem gaps and ways to stimulate demand for circular food in the country.

Speaking on the launch of this initiative, Mr. Anish Kumar of Transforming Rural India Foundation said, “TRIF is wedded to the idea of adoption of circular practices in production of food while ensuring a sustainable increase in smallholders’ incomes and helping the consumer access safe food in a manner that is friendly to our planet.”

Mr. Santosh Kumar Singh, Director, Intellecap said, “Agriculture has been one of the core focus areas for Intellecap since its inception. Given the need for closing the loops for materials and substances in agriculture and food sector, which includes reducing food loss and waste, this platform will help in making the agriculture and food systems in the country circular while increasing the incomes and resilience of the smallholder farmers, helping the businesses achieve triple bottom lines and consumers access safe and healthy foods and maintaining sustainability of our food and agriculture systems.”

Despite bringing with it several economic and environmental advantages, circularity in agriculture has failed to spread its wings in India. Limited awareness of the benefits of practicing circularity in agriculture among farmers and consumers, fragmented innovation ecosystems, and a weak and deeply flawed positioning of circularity among farmers are some of the roadblocks hampering the adoption of circularity in agriculture. Intellecap-Transform Rural India Foundation (TRIF) partnership has devised a four pronged strategy to mitigate these challenges and realize a self-sustaining circularity ecosystem in India: (i) Identifying the ecosystem gaps which exist (finance, policy, consumer awareness, etc.);(ii) bridging these gaps through collaborations; (iii) Improving the economies and business case for circular agriculture through value addition and certification; (iv) Catalyzing on-ground action to support test bedding, piloting and scaling of identified innovations.

With 30% of land in India degraded, 25% of the water which is used for producing food wasted, and farmers losing over US$ 12 billion as post-harvest losses makes adoption of circular practices in agriculture is extremely important. According to research conducted by ICAR, 85.5 megatons of carbon emissions could be reduced in India by simply adopting practices like those followed in circular agriculture. Further, Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimates that practicing circularity in agriculture could lead to an annual economic benefit of US$ 61 billion in India by 2050.

Reports & Policies

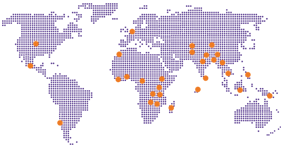

Our Impact Map

Sign up for our newsletter

© Copyright 2018 Intellecap Advisory Services Pvt. Ltd. - All Rights Reserved