Microsoft, Frontier Markets & Saral Jeevan join hands to train 30,000 rural SHG women in AI- Coverage by The Statesman at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025

Intellecap & IDH Blog | Accelerating Net-Zero Transitions in Agriculture and Food Systems

As climate change accelerates, transforming agriculture and food systems to reduce emissions has become a global imperative. Technologies for a net-zero transition in agriculture and food systems are playing a critical role in complementing existing climate action initiatives.

Intellecap & IDH are jointly studying these technologies to better understand their potential use-cases in mitigating emissions and how they can be integrated into businesses, governments, and developmental agencies’ strategies.

This article provides an overview of the ongoing study and highlights some early findings related to emission hotspots, technology use-cases, benefits, and principles related to adoption in the smallholder context.

A Farmer’s Struggle: The Impact of Climate Change on Smallholder Agriculture

Imagine a smallholder farmer in a low-income country, let’s call him Rajiv, who has been cultivating maize for generations on his family’s land. Over the years, he has witnessed the effects of climate change firsthand. Erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and the increasing prevalence of pests and diseases have made it more challenging for him to maintain a stable crop yield. The rising cost of fertilizers and other farm inputs has only added to his financial burden. Rajiv is aware that his agricultural practices contribute to greenhouse gas emissions, but he feels powerless to change the situation.

Rajiv’s story illustrates the challenges faced by smallholder farmers worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). These farmers are not only struggling to adapt to the changing climate but also grappling with their role in the global emissions problem. The urgent need for net-zero transitions in agriculture and food systems calls for innovative solutions that address the unique challenges faced by farmers like Rajiv……

-

ShareInstant khabar | December, 30, 2025

संकल्प भारत समिट में सीएम योगी के ट्रिलियन डॉलर अर्थव्यवस्था के विज़न को मिला समर्थन- Coverage of the 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by Instakhabar

-

ShareInstant Khabar | December, 30, 2025

Sankalp Bharat Summit-25: लखनऊ में उद्यमियों का जमावड़ा, महिला आंत्रप्रिन्योर्स की ज़ोरदार भागीदारी- Interview of Ajaita Shah, Founder & CEO, Frontier Markets at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by InstaKhabar

-

ShareInstant Khabar | December, 30, 2025

Sankalp Bharat Summit: टेक्सटाइल सेक्टर में महिला आंत्रेप्रिन्योरशिप बहुत मज़बूत- Venkat Kotamaraju, Partner and Director, Intellecap speaks to InstaKhabar at the 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025

Leveraging community leaders to build resilience against climate change in urban areas (Comment)

While cities cover only two per cent of the global land area, they contribute around 70 per cent of the global greenhouse emissions, one of the main drivers of climate change.

The UN forecasts that urbanisation and population growth could add another 2.5 billion people to urban populations by 2050, with almost 90 per cent living in Asia and Africa. Consequently, the urban contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change will only increase with time.

As a response, various stakeholders have designed climate change resilience products including cool roofs, home insulations, drip irrigation solutions and solar home systems that have seen heightened interest in India. While such products have seen a market, the uptake is concentrated among the richer sections.

The urban poor, who constitute almost 30 per cent of India’s urban population, do not have the knowledge or the capacity to pay for such products. It has always been a challenge to symbiotically combine all four components (informed customer targeting, low-cost marketing, innovative distribution and sales, and nurturing consumer goodwill) to design a marketing strategy for the urban poor. As a response, some organisations have started leveraging community-level leaders (CLLS) as marketing channels for such products.

The rationale for the CLLs comes from the effectiveness of the model in building long-term products resilient to climate change while simultaneously creating livelihoods. Some best practices that can be used to strengthen the efficacy of the CLL mode are:

* Design a product identification framework tool: Each product should be analysed on the basis of four parameters: a) demand for the product (number of households), b) affordability (price), c) profitability (percentage of price), and d) scalability (potential demand across different urban agglomerations). On the basis of analysis, only those products which score high on all parameters should be offered to the market.

* Conduct on-ground demand assessment: Understanding the customer becomes more important in such cases, particularly since the customers knowledge of the product is limited. Hence awareness levels, willingness to pay and customer demand becomes more critical. Such an on-ground assessment can help further shortlist products for a particular set of homogeneous households.

* Provide easy financing options: It is beneficial to help CLLs establish close networks with MFIs and other financial institutions to provide financing facilities to potential consumers, hence enhancing their ability to pay and increasing uptake.

* Segment CLLs based on skillsets and motivation: Classification of CLLs as per their sales skills and motivation is essential for success. Selling different products require different skillsets and a quick analysis can help in this matchmaking. Some parameters which can be used to assess skills include age, educational qualification, business experience, and technical skillsets.

* Capacity building: CLLs need a certain degree of training and it is observed that CLLs find it easier to sell better when trained rather than through close association with their communities.

* Build ownership in CLLs: Instead of making the product available free-of-cost, CLLs should be asked to invest in the product. If required, finance should be made available by partnering with co-operative banks and MFIs; that way one can build ownership in CLLs.

* Design standardised operational procedures (SOPs): Since the business model includes partnerships both with CLLs and product manufacturers, it is necessary to design SOPs to simplify the entire delivery process.

Inexpensive Impact: The Case for Frugal Innovations

Over 4 billion people around the world face unmet needs in core areas such as food, water, energy, health-care and housing. The market potential for these low-income populations is huge: Approximately 4.5 billion low-income people globally represent an annual purchasing capacity of US$ 5 trillion (PPP), with India, East Africa and South East Asia accounting for a sizable chunk of this market. Yet servicing this market is fraught with challenges, including customers’ limited ability to pay, poor infrastructure and latent demand. Catering to this market requires frugal innovation, which is about transforming adversity into opportunity, enhancing value and ultimately doing more with less, thereby impacting more people.

Many firms – both startups and corporates – have begun to design frugal, market-based solutions that include product and business model innovations to meet the unmet needs of billions of underserved customers. In Kenya, for example, Pad Heaven makes re-usable sanitary towels from banana fibers, and Ecopost uses plastic and agricultural waste as a resource to manufacture sustainable materials for the building, construction and transport industries. India is also a hotbed of frugal innovations, which spread across sectors. For example, Saral Designs markets an automatic machine that allows organizations to produce low-cost sanitary napkins, Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Smiti provides the Jaipur foot – a low-cost prosthetic leg, and Banka Bioloo sells sanitation systems that eliminate the need for off-site disposal of human waste. Each of these products highlights how such innovations can be game changers.

But frugal innovations are not just about products: Great potential also lies in business model innovation. Frugal innovations in services can include deep specialization in a niche segment of a huge market, tiered pricing systems and efficient use of human capital. These innovations respond not only to a lack of skilled human capital, but to an institutional void. For instance, Unilever’s small, affordable detergent sachets are priced at a more palatable level for the low-income populations in India and Africa. And Aravind Eye Care’s approach to performing cataract surgeries at large scale without compromising on quality highlights how process innovation can ensure inclusivity and service delivery in a sustainable manner.

Frugal innovation is also not limited to low–tech sectors. It can require, or be combined with, frontier science and technology. Products like Swach a high-tech portable water filter developed by Tata, HealthCubed Inc.’s Health Cube – an integrated, tablet-based, portable point-of-care diagnostic test device, and Agatsa’s pocket-sized 12-lead electrocardiogram have demonstrated how technology can not only be an enabler but an amplifier to both product and process innovations.

Lessons for the Circular Economy

While frugal innovations are commonly associated with developing economies, these innovations are not only for resource-constrained users – and they also address the issue of resource scarcity. The current “take, make and dispose” economy is not sustainable. Economic productivity is already being curbed by the rapid depletion of existing and readily available natural resources. These constraints require a shift in thinking towards a more circular model focusing on resource productivity, and a shift towards a “make, share and remake” model. This will be a key driver towards sustainability for frugal innovations of the future.

Principles from frugal innovations are directly applicable to this circular economy, as generating value from waste is common across African and Indian startups. For example, Kodjo Afate Gnikou built a $100 3D printer from electronic waste. And in Europe, the firm Qarnot has developed QH.1, a high-performance computing server that uses “waste heat” from its microprocessors to heat homes and other buildings.

Smart villages: Driving development through entrepreneurship

Over 68 percent of India’s population lives in rural areas. There has been a gradual increase in migration from villages to cities primarily for livelihood opportunities, better education, and healthcare facilities, among others. The rising burden on urban cities due to migration emphasises the need to transform villages so that they can meet the critical as well as aspirational needs of the villagers. This can be done using innovative technologies and transforming the service delivery models for villages. Transformed villages are called Smart Villages.

While the phrase ‘Smart Village’ has become a buzzword in policy and rural development discussion, there is no universal definition of such villages. Two things that are common to all Smart Villages are the extensive use of technology and integration of several key interventions in infrastructure and service delivery.

It’s an integrated approach of delivering access to skills and quality basic services including education, e-health, 24×7 power, safe food, among others.

There are numerous initiatives supported by the government, and spearheaded and supported by corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives and philanthropic institutions.

The Government of India launched the Shyama Prasad Mukherji Rurban Mission (SPMRM) in 2016, with the objective to spur social, economic and infrastructural development in rural areas. The mission aims at making villages smart and growth centers of the nation. In its first phase, it targeted to develop a cluster of 300 Smart Villages over the next three years across the country. Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana, which envisages integrated development of selected villages was another step taken by government in this direction.

While the government-led initiatives rely on integration and convergence of the existing central and state government schemes to develop these Smart Villages or clusters, the CSR initiatives are generally more innovative in terms of implementation and use of technologies. For example, smartphone-maker Nokia has launched a Smartpur project which aims to create a sustainable ecosystem where community members can leverage digital tools to bring efficiency in daily lives. It aims to bring transparency in governance, economic prosperity for households and ease of access to various government services and information.

Tata Trusts supports agriculture intervention for tribal communities under its Lakhpati Kisan – Smart Villages program. While these CSR or philanthropic institutions do work closely with government institutions, their model of engagement and the partnership with the government vary significantly.

These initiatives have provided key learnings to empower institutions, build engagement models and frameworks for planning, and developing implementation strategies for Smart Villages.

We suggest learning from the Smart Cities mission, but we also caution that these learnings must be contextualised and synthesised, as Smart Villages are very different from Smart Cities. The latter are more focused on increasing the overall efficiency and improvement in civic infrastructure, while Smart Villages envisage the need of building the facilities from scratch.

One of the key challenges in developing Smart Villages is ensuring their sustainability. This can only be addressed if we build our Smart Village strategy with entrepreneurship at its core. Thankfully, India has one of the most vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem that is working towards addressing rural development challenges using innovative technologies and business models.

We have enterprises that are addressing healthcare needs (Glocal Healthcare Systems, mHealth, iKure), delivering quality education (Gyanshala, Hippocampus, Avanti), providing decentralised energy solutions (Sun Moksha, Mera Gao Power, Mlinda), transforming agriculture productivity (Ekgaon, Jain Irrigation, Milk Mantra), providing drinking water and sanitation services (Sarvajal, Svadha, Banka Bioloo), creating livelihood opportunities for women (Dharma Life, Frontier Markets, Sudiksha Knowledge Solutions), and so on. The need is to integrate this approach for the Smart Village vision.

-

Microsoft, Frontier Markets & Saral Jeevan join hands to train 30,000 rural SHG women in AI- Coverage by The Statesman at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025

December, 30, 2025Share

-

संकल्प भारत समिट में सीएम योगी के ट्रिलियन डॉलर अर्थव्यवस्था के विज़न को मिला समर्थन- Coverage of the 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by Instakhabar

December, 30, 2025Share

-

Sankalp Bharat Summit-25: लखनऊ में उद्यमियों का जमावड़ा, महिला आंत्रप्रिन्योर्स की ज़ोरदार भागीदारी- Interview of Ajaita Shah, Founder & CEO, Frontier Markets at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by InstaKhabar

December, 30, 2025Share

Microsoft, Frontier Markets & Saral Jeevan join hands to train 30,000 rural SHG women in AI- Coverage by The Statesman at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025

संकल्प भारत समिट में सीएम योगी के ट्रिलियन डॉलर अर्थव्यवस्था के विज़न को मिला समर्थन- Coverage of the 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by Instakhabar

Sankalp Bharat Summit-25: लखनऊ में उद्यमियों का जमावड़ा, महिला आंत्रप्रिन्योर्स की ज़ोरदार भागीदारी- Interview of Ajaita Shah, Founder & CEO, Frontier Markets at 2nd Sankalp Bharat Summit 2025 by InstaKhabar

Reports & Policies

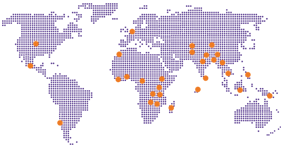

Our Impact Map

Sign up for our newsletter

© Copyright 2018 Intellecap Advisory Services Pvt. Ltd. - All Rights Reserved